American Fascism in the Federal Period [UNLOCKED]

Want historical parallels to the current rise of US authoritarianism? Me neither! — but the most obvious place to look is routinely ignored by those who do.

[TEMPORARILY UNLOCKED]

You may be aware of the ongoing current public disputes among anti-MAGA intellectuals over the question of Trump and fascism, and the last thing I’d want to do is rehash it. I find the subject personally annoying for the unsophisticated reason that if Trump were finally proven beyond a reasonable doubt to be fascist, or not fascist, I wouldn’t feel or think any differently about him, Trumpism, or anything else. A more advanced position has it that the question matters because improperly identifying the threat he poses obstructs forming an effective resistance. I’m just not that advanced.

Anyway, the public argument sometimes sounds to me less like an urgent discussion, with the potential to help the rest of us develop a point of view, than like mutual vituperation among a few smart people. Ultimately unhelpful, like so much discourse, to doing anything.

Regardless of whether Trump can be proven fascist, though, I have been impatient for about eight years now, ever since he was elected (seems like forever) with what looks to me like an obsessive effort to identify the supposed historical parallels, and the supposedly immutable steps in democracies’ succumbing to authoritarianism, and other supposed expertise supposedly useful to resisting Trumpism, provided by historians supposed to know how it supposedly was, back when something similar was supposedly going on. Timothy Snyder, a scholar of the rise of European fascism in the 1930’s, sees useful parallels, not surprisingly, in the rise of European fascism in the 1930’s. Heather Cox Richardson finds parallels in her field, the U.S. Civil War and the collapse of Reconstruction. Others do the same.

I’ve criticized this tendency quite a bit during the past eight years—here, here, and here, for example—so again, won’t rehash. But what keeps striking me, now, about the big history pile-on, and in particular about the Americanists involved, is how far back in our national history they’re not willing to look.

The dire historical Trumpist resonances most favored by U.S. historians (working backward here) are, working backward:

U.S. Nazis during WWII; the racist system of violence known as Jim Crow, with its concomitant “Lost Cause” mythos; and the successful effort, both political and violent, by the white South to demolish Reconstruction programs for equalizing rights in the defeated former Confederacy.

That line of events isn’t presented as merely resonant. In Richardson’s work, for example, events of the 19th century serve as a direct explanation: for her, the rightism flowering in Trumpism developed directly out of racism migrating after the Civil War out of the white South and throughout the country.

In criticizing that angle, I’ve complained that tracing Trumpism to the 19th century doesn’t just have the credibility problem that comes from making claims of current all-importance on a period whose importance the relevant historians already have a professional stake in promoting. The line also enables not taking into account any role that the politics of the past fifty years or so may have played in fostering conditions for Trumpism. I suspect that’s because looking at more recent events would implicate not only the modern Republican right but also Democratic legislatures and presidential administrations, beginning with the one-term Carter presidency and including the Clinton and Obama years.

But lately I’ve been noticing something else. It’s not only the recent past that’s been transformed, in these warnings about national tendencies and historic tides, into a gigantic blank spot. The rampantly antidemocratic authoritarianism of a more distant past—the country’s founding period—becomes a blank spot too.

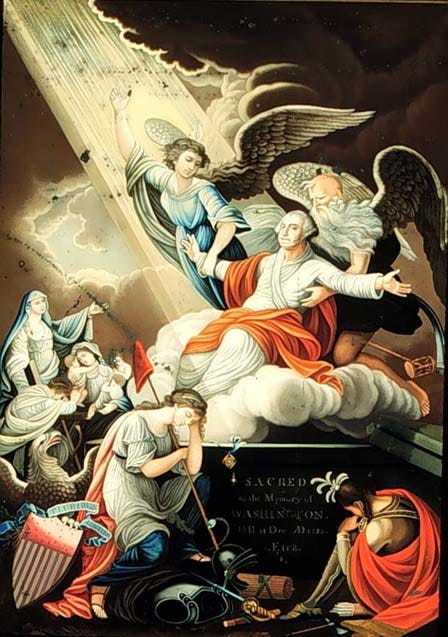

At times the founding period even gets framed as the ideal to which we should be harkening in support of saving democracy (“George Washington warned us about Trump”). And given everything that went down during the first two presidential administrations—and given the nature of the ideology and oratory known as “High Federalism”—that’s just weird. Because I’ve written a lot about that period’s authoritarianism, and how Hamiltonian economics and finance connected with it, I’ve even been asked if it’s fair to call the High Federalist ideology—and Alexander Hamilton himself—fascist.

I’ve always thought that would be weak and dry, an academically taxonomic way of construing 18th-century American authoritarianism—that looking back through modern categories makes it harder to understand Federalist anti-democracy on its own terms. Obviously, current resonances are everywhere in history. Fights that went on during the Federalist period can seem, as I note in the introduction to my forthcoming book, The Hamilton Scheme, both unutterably strange and strangely familiar. But giving them twentieth-century labels makes the past seem only a distant foreshadowing of more familiar, concrete, and modern events, thus robbing the past of its own intensity.

But hey! If we’re really supposed to be rummaging in the nation’s past for more or less harrowing examples of authoritarian tendencies in our society and the militantly anti-democratic ideologies that hymn the sanctity of such authority, then there’s no better place to look than 1789-1804, with the rise and fall of the Federalist Party. That story has it all: militarism, violation of individual rights, censorship, flirtation with secessionism, worship of a charismatic leader, conspiracism, horror of immigrant influence . . . all wrapped up in a concerted attack on democracy.

And yet the founding majority political party doesn’t even come up when historians are making warnings about Trump and his origins. Worse, that period is held up as a model for #resistance. That fantasy is painfully revealing of the tottering condition of the liberal politics and civics on which these warnings and idealizations are so often built.

And that—along with MAGA—is what scares me.

One quick example to chew on. It’s a possibly somewhat startling fact about George Washington that when his administration came under intense criticism in 1793, and an emerging permanent opposition formed, with political organizations promoting candidates, writing petitions, signing resolutions, and generally grousing, Washington insisted that the very existence of such organizations was unconstitutional. He wanted them shut down by executive force. In some cases, he wanted petitioners and signers of resolutions prosecuted.

That’s an outrageous abuse of presidential authority, from our point of view, and from the point of view of many then (including Attorney General Edmund Randolph, who declined to carry out the president’s wishes). Washington is sometimes admired today for warning against the rise of parties. Viewed realistically, that warning tracks closely with his rigidly authoritarian attitude about political opposition. To him, the term “loyal opposition” was self-contradictory: what he meant by “party” was any form of organized minority, which in his eyes forever verges at the very least, by virtue of its being organized, on treason.

“Self-created societies,” as he called them, were “pernicious to the peace of society.” A “professed democrat,” he said elsewhere, “. . . will leave nothing unattempted to overturn the government of this country”; organized, sustained dissent, that is, represented an attack on the United States itself. (He also fretted about a malign influence that he thought was being secretly exerted on U.S. politics by the Illuminati.)

In future posts here and there, I’ll give other snapshots of the period that show what I’m talking about, and I’ll consider how and why the history #resistance fuzzes these snapshots out. While mine is decidedly not an Antifederalist or Jeffersonian critique, certain other great Federalist founders won’t come off any better than Washington, big and less big names, critical both to the invention of federalism as a system of government and to the rise and fall of the Federalist Party: John Adams, Timothy Pickering, our boy Hamilton, James Wilson, Robert Morris, and others. (Don’t come off well by the standards of our time, we always have to say—but as we’ll see, also by the standards of some in that time!).

The point here isn't that these anti-democratic, authoritarian founders caused or even presaged Trump. That’s not my shtick.

The point is that the founders wove into the national government elements of the kind of authoritarianism we now rightly fear. It's therefore taken a lot of work, over centuries, to begin to expel those elements—to overcome our founders’ intent and to foster democracy. To the extent that historians who are now sounding warnings don't get that, or ignore the historical realities for political reasons, their warnings should fall flat.

______________

Further Reading

A book review in The New Yorker nicely summarizes the prevailing arguments about Trump and fascism.

Agree about Moses, interesting comparison.

I’ll be very very interested to see how you link a brand new experimental democracy with the conditions and dynamics of late 20th and early 21st century superpower America / I’ll be looking out