[THIS PAYING-SUBSCRIBER-ONLY POST IS TEMPORARILY UNLOCKED DURING THE CONGRESSIONAL INVESTIGATION OF EVENTS OF JAN. 6.]

As law enforcement seeks to arrest, charge, try, and punish people involved in events at the Capitol Building on January 6, and the Senate tries former-President Trump for inciting it, questions have been coming up regarding what the hell that hellish event really was. Sedition? Attempted coup? Riot? Trespass? Rebellion? Insurrection?

All of the above, possibly—the terms aren’t mutually exclusive—but to me, the closely related concepts of “rebellion” and “insurrection” seem especially resonant because they’ve often been used to characterize pivotal uprisings in our national past. So does January 6 really count as an insurrection? Let’s see:

The attack on the Capitol was a violent effort not to protest, and by no means simply to vent frustration and exert pressure by running riot, but to prevent operations of the national government. The specific operation targeted by the attackers was the representative branch’s certifying the election of the covalent executive branch. The purpose of the attack was to overturn the constitutional electoral process by force and thus keep Donald Trump illegally in office. That, at least, was the hope of many in the crowd.

If that doesn’t count as an insurrection, I don’t know what does.

A shocking one, too. In no other insurrection in our history has a crowd forced its way into the Capitol. No other insurrection was openly incited by the executive branch. Those achievements are unique to Trump.

Some argue that because the January 6 effort failed its purpose—it halted but didn’t prevent the certification—it doesn’t count as an insurrection. But failure may be one of the key things about insurrections. We tend to call successful overturnings of government revolutions, and new governments created by revolutions tend to celebrate the revolutions that created them and to disparage, as insurrections, any efforts to unseat them.

In those terms, the most important insurrection in our history—it began with riots, shutdowns, and crowd attacks on officials and law-compliant citizens and then became a full-on insurrectionary war of secession—was the American Revolution, as it became known after it succeeded. During that war, the British naturally called it both an insurrection and a rebellion. Our other insurrectionary war of secession was the Confederacy’s effort in the Civil War, ultimately unsuccessful. We sometimes call that war both an insurrection and a rebellion.

Having two critically important insurrectionary wars in our history may give us an ongoing problem. The successful one made us; the unsuccessful one stands as our moral watershed. Rebellion and internal strife and calls to the barricades on behalf of fundamental rights can seem wired into a national romance over whatever’s supposed to make us American. The romance is evidently pretty easy to play to.

Maybe that’s partly because there was insurrection here even before there was a country here. The colonial period saw a slew of uprisings, usually named after their leaders: Bacon’s, in 1675; Culpepers’s, in 1679; Coode’s, in 1689; Leisler’s, in 1689.

Then, shortly after the Revolution, horror among upscale Americans caused by the Shays Rebellion—it’s named after one of its leaders, Daniel Shays—contributed to the decision to form a national government. In that negative sense, the Shays Rebellion was the inverse of the January 6 insurrection: it didn't seek to destroy the Constitution but helped, if unwittingly, to create it.

The Shaysites were poor farmers and artisans in western Massachusetts, veteran footsoldiers of the Revolution. Sent home unpaid, they suddenly found themselves subjected to crushing new taxes, not for public benefit, but earmarked for paying 6% tax-free annual interest to the small group of upscale Americans who had invested in the war as a financial speculation. If you couldn’t pay these taxes—most couldn’t—you and your family went to jail and your land, tools, and livestock were seized. Meanwhile, Massachusetts had tightened up its voter qualifications to keep the poor from having a voice in such legislation.

For former soldiers in the Berkshires, all of this was deeply disappointing—with the British gone, they’d hoped for a more equitable society—and in 1786, they marched against the federal armory in Springfield. The state government, freaking out, eased the tax laws. Now rich war investors couldn’t see where their profits would come from, and rumors flew among elites all over the country that the Shaysites’ ultimate plan was to take over government and dictate that all property in America be held in common. That was only partly paranoid conspiracy-mongering. Some of the rebels really did dream of that kind of thing.

And the Continental Congress had no legal power to suppress such insurrectionists militarily. It was the state militia and a private militia, surreptitiously aided by the Congress, that finally prevailed against the Shays rebellion; in response to it and other unrest over economic inequality, upscale leaders gathered in Philadelphia the following year to find new ways of pushing down what Edmund Randolph of Virginia, opening debate on the Constitution, explicitly called “the democracy.” The Constitution created strong federal powers to enforce tax collection throughout the states for the profit of the lending class, as well as to put down insurrections. Samuel Adams, sometime leader of insurrectionary efforts in Boston against the British—efforts precisely against unfair taxation!—called for hanging the Shaysites.

The Shays Rebellion may be called wrong, and it was certainly wrongheaded. Still, unlike the January 6 attack on the Capitol, it was a rebellion for marginally greater equality, fairness, and democracy—not for top-down, monarchical autocracy.

There’s another category of American insurrections that’s even easier to sympathize with: slave revolts, as they’re commonly known. They went on in the colonial period and continued through the antebellum years.

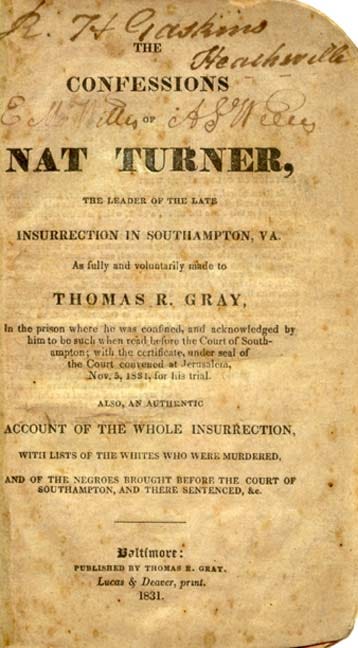

The term “revolt” somehow makes resistance by the enslaved sound less like insurrection and more like spontaneous uprising and escape—more like a prison break—and it was long written off that way. Recent scholarship, however, has clarified how misleading that sense is. Some of these rebellions were carefully planned, well organized, and involved military discipline: the Stono Rebellion, in South Carolina in 1739; and Nat Turner’s Rebellion, in Virginia in 1831, for example. Because this type of rebellion was against owners of the forced labor camps known as plantations, it might seem to differ categorically from rebellions against governments, but the plantation system was a key aspect of government, and both the Stono and the Turner rebels fought pitched gun battles against opposing forces of official colonial and state militia, respectively.

Probably the most famous insurrection on behalf of the enslaved was led by the ever-fascinating John Brown, a white man, in 1859. His goal was to seize weaponry and ammunition from the federal armory and arsenal in Harper’s Ferry, Virginia; widely distribute it to enslaved populations; and trigger a rebellion to take down the whole evil institution. That didn’t happen, of course. Brown’s attempt to hold the arsenal against U.S. Marines, led by Robert E. Lee, collapsed quickly.

But the insurrectionary nature of the dream at Harper’s Ferry survived in an unusual form. During the Civil War, one of Brown’s Boston-abolitionist supporters, Thomas Wentworth Higginson, raised a U.S. Army regiment of escaped black fighters in South Carolina and Georgia and led them against their oppressors. The regiment included the army’s first black nurse, Susie King Taylor. The Union thus not only defeated the Confederacy’s insurrection but also, by arming former slaves, supported a kind of insurrection against the Confederacy. That was John Brown’s dream.

And finally, the horrible flipside: the Wilmington insurrection of 1898.

This one has the nastiest kind of reverberations. They echo back to the Civil War. And they echo forward to January 6, 2021.

Then the biggest city in North Carolina, and with a majority black population, Wilmington had managed to hold off the total demolition of Reconstruction, thanks to a remarkable political alliance of white labor-movement populists and black middle-class political leadership. In 1898, therefore, a group of white supremacists—they’d held what they called a White Supremacy Convention, attended by 8000 people—launched a campaign of terror in the city. Led by the Red Shirts paramilitary organization, the terrorism went on for days. They burned and tore down black-owned businesses and homes. They demanded the total formal submission of the black population. Then they escalated, taking weaponry from the armory and making outright war on the city’s majority-black neighborhood, attacking the families there with gunfire; murder estimates range from sixty to 300. The state governor, treating the situation as a “race riot,” sent troops in to suppress black and white alike. Meanwhile, the white supremacists held the mayor and city council at gunpoint, forced them to resign, installed an unelected, all-white government, expelled black politicians from the city, and paraded white allies before crowds and then expelled them, too. With nothing left in Wilmington, many other black citizens began leaving town. The next year, the unelected white-supremacist government was formally elected.

The Wilmington insurrection thus became not only a rebellion against government but also a full-fledged military coup—a revolution, really—its success legally formalized; it has a special place in the history of reestablishing white power in the South after the Civil War. Ending Reconstruction in other states involved intimidation and violence too, of course, but because of the biracial alliance in Wilmington, white power in North Carolina had to resort to outright massacre of the black population and outright overthrow of a duly elected government. 1901 saw the departure from the U.S. House of Representatives of George White of North Carolina, the last black representative from the whole Reconstruction South, and it would take more than ninety years for North Carolina to send another black person to Congress. Affirming a concerted white-southern rejection of the U.S. Constitution, the extremist coup at Wilmington served as a model for the whole white power structure throughout the South, an ever-present image of just how far white supremacists were willing to go, and just how effective they could be. Bragging about the coup, by white people in North Carolina, went on within living memory.

That uprising was not, putting it mildly, on behalf of American democracy, equality, and freedom; it was on behalf of American tyranny. And while it was overwhelmingly successful, maybe we can’t deal with its success. In violation of the usual terminology, we still call events in Wilmington not a revolution, but an insurrection.

Further Reading

Skim

The Constitution Center notes here that the Shays Rebellion was a prime inspiration for the Constitutional Convention (while characteristically denying the economic issues involved).

Here’s a quick overview of some key slave revolts.

Swim

This article, with pics of furniture, etc., gives a flavor of the 1775 Boston crowd attack on the home of the royal governor of Massachusetts. The title quote from the scene, “such ruins were never seen in America,” is misleading: this kind of riot was common in the colonial period.

Henry Knox to George Washington, freaking out about the Shays Rebellion.

On the long legacy of the Wilmington coup.

Dive

The slave revolt planned by Denmark Vesey has led to a lot of scholarly wrangling. This piece is brief, but it gets into the historiography.

Susie King Taylor, the first black nurse in the U.S. Army, formerly enslaved, wrote an amazing memoir, in full text here.