Collusion, Theft, Violence, Lies: Lurid Tales of American Elections, 1788 – 2020

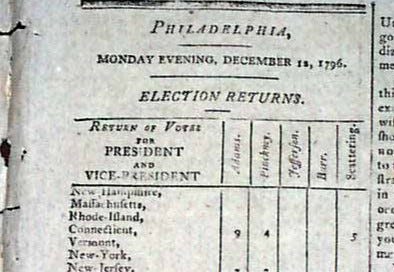

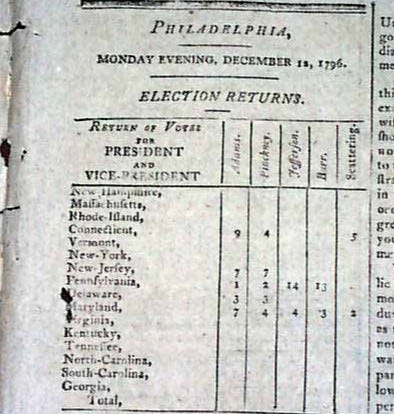

Entry No. 1: 1796, our first contested presidential election

Cheery concept, eh?

This occasional BAD HISTORY series will be my way of doling out intense doses of a counter-irritant to the looming fact of the 2024 presidential election. As an engaged citizen of the republic, operating under some degree of discipline as a writer, I consider it way too early for me to be thinking closely about that upcoming event (the same, I know, doesn’t hold for some of you!). But for anyone in nonfiction book publishing, the election already represents a looming nightmare.

The nightmare now occurs every four years. As hard as it is to get any attention for a nonfiction book published in any year, it becomes impossible to get any attention for anything unrelated to the election in an election year.

I’m pretty sure things weren’t always like this. Didn’t people who buy nonfiction books once find topics other than presidential elections entertaining? Nowadays they’ll desultorily poke at other topics, as long as there’s no presidential election to read about, but when there is one, forget it: the election is the default. There’s no way to compete with it.

So instead of quailing, yet again, in the face of this quadrennial challenge to getting ahead in publishing, instead of running cravenly away or glaring sweatily at the calendar and trying to bob and weave my way around certain stark chronological facts, this time I’m turning and fighting back! Here on BAD HISTORY, I launch this grimly titled series and make a dead-on attack on the 2024 election with a set of brief, lurid tales of U.S. elections past. Which will, in the end, of course include 2020.

The inspiration for this ongoing collection of posts, to appear occasionally between now and Election Day 2024, is the fact that while not every U.S. election, it turns out, went horribly, it’s amazing how many did. I’ve already told you some of those stories, and don’t worry, I won’t repeat myself in this series. In a single post, I once told you about Hamilton’s fixing the first presidential election, LBJ’s stealing his first Senate seat, the Brooks Brothers riot, and Nixon’s collusion with South Vietnam. (What was I thinking—that’s like four posts right there. I was new to this.) I also told you about 1876.

So today, let’s look at 1796.

I won’t be doing this whole series in chronological order, but to begin the series, we really must dive into the country’s first contested presidential election. It’s peculiarly relevant to recent elections. For one thing, 1796 was distinguished by a new role for the partisan gutter press of the period. (Today we just call it the news.) There are other connections too.

A quick refresher on the situation in the day. In September of 1796, George Washington announced a decision to end his presidency with the end of his second term. There’s a commonly held notion that Washington was thereby setting a precedent for a tradition of presidential term limits that went unbroken until the third term of Franklin Roosevelt, but that was by no means the first president’s intention. Washington is on the record opposing term limits—by law or tradition. The Federalist Party even toyed with bringing him back for a non-consecutive third term in 1800. So widely admired was Washington that the plan was rendered only slightly less feasible by his death in 1799.

Washington was just done in ‘96: exhausted, frustrated, forgetful, bummed, eager to give full-time attention to his massive, complicated business ventures. Also: if he had stood for office again, despite his popularity the election might not have been unanimous. Not a great way to go out. He stepped down.

So here was a new and anxiety-provoking situation: a contested presidential election only eight years into the life of the national government. But America being America, we harkened to the better angels of our nature, rose to the challenges, overcame our differences, and did ourselves proud. . . !

Not really.

That would be boring. We’ve rarely been that.

The major candidates that year were the incumbent Vice President, John Adams, and the opposition party leader, Thomas Jefferson. They’d once been friends and allies. Now they were enemies and opponents. Things had gotten rough since those heady days of 1776, when the fussy, bustling, shortish, overdessed Yankee had recruited the philosophical, mercurial, lanky, sometimes shabbily attired Virginian onto the committee to draft the Declaration of Independence. For one thing, that Declaration, which nobody much cared about in 1776, had turned into a bit of a thing, inflaming Adams’s ever-flammable jealousy: Jefferson was getting all the credit for it. More important to their conflict, however, was the zero-sum partisanship that roiled the 1790’s governing elite. Adams was the Federalist Party Vice President in a Federalist Party administration. Jefferson had quit that administration in order to head the opposition becoming known as the Republican Party. They found themselves on opposite sides of what felt to both sides like a fight to the finish.

Yes, “partisan”—and yes, “parties.” I know there’s a sense that the founding generation didn’t believe in parties, couldn’t see them becoming a major factor in American public life. That’s an area where the founding generation was quite full of it. When they loudly excoriated parties and partisanship, they meant their political enemies: parties were considered bad, so each party called the other a party. Washington, in his famous farewell speech, warned against the development of parties. He meant the Jeffersonian opposition, and Washington was in fact the leader of a party. Hamilton, Burr, Jefferson, Madison, Adams, et. al.: by 1796, they were all party operatives.

True, the Federalists and the Republicans weren’t, like our modern parties, organized for mass electoral politics. That’s because there was no mass electoral politics. The masses couldn’t legally vote. This game was limited to white men holding sufficient property—with even more property required to hold elected office.

And yet in 1796, the Republican opposition was already beginning to get organized in a recognizably party-like way. (This was the ancestor not of today’s Republican Party but of today’s Democratic Party. To avoid confusion, historians often refer to Jefferson’s party as Democratic-Republican, but I prefer to use terms people used at the time.) The Republicans were in the minority, so they had to scramble, to a degree that the Federalists thought they themselves didn’t have to, and in that way, the Republicans got ahead of the Federalists in interstate organizing.

So that’s a sketch of the situation in play around Adams vs. Jefferson, 1796.

Adams won, by the way.

There won’t be a lot of suspense in this election series. Still, it was very close—highly suspenseful at the time—and the process pointed the way to the future of American elections, as that fall saw a hurricane of over-the-top invective, insult, fake news, and scurrilous allegation.

The prevailing idea wasn’t that grave policy differences existed and voters should choose a candidate based on informed opinions about those differences. The prevailing idea was that the very fate of the nation hung in a dangerous balance, with each side, according to the other, dedicated to the immediate destruction of the republic, which could be saved only by a proper outcome in this particular election. The next time we're told, “Vote as if the fate of the country depends on it—because it does,” and "This is the most decisive election in American history,” we might remember that our existential religious-drama approach to political contests has deep roots in our earliest presidential contest. Maybe there’s even a self-fulfilling prophecy involved.

The media, as it was not then known, became the main site for this first supposedly existential contest over the supposedly fundamental meaning of America. Papers in those days didn’t even try to appear objective. Writers published pseudonymously, and there was no premium on supposed accuracy, no penalty for blatant inaccuracy. Jefferson supporters, labeling Adams “His Rotundity,” claimed that the Federalists planned to install a monarchy in America (fact-check says false). Adams’s supporters claimed that Jefferson was an anarchist (false) who wanted to unleash a French-Revolution terror in the U.S. (false) and even—horrors—emancipate the enslaved (false). The Gazette of the United States, a Federalist paper, alleged that Jefferson was sexually involved with one of his slaves (true) and had fled during the Revolution (this needs context).

Hamilton, for his part, was working against Adams, the candidate of Hamilton’s own party, trying to get southern Federalists to withhold votes for Adams and thus get Charles Pinckney of South Carolina elected instead. That scheme came to light, inspiring Adams’s life-long fount of invective against Hamilton —including the famous “bastard brat of a Scotch peddler,” but it got a lot worse than that. The Federalists, though a majority, were having trouble functioning as a unified entity.

Then, in January of 1797, with the returns still coming in, one of Jefferson’s paid hacks and dirty-tricks guys, James Callender, published an allegation that Hamilton had had an extramarital affair with a Mrs. Reynolds (true). That news had actually been around awhile: early in the decade, the Jeffersonian group had been hoping to prove Hamilton guilty of corruption at the Treasury (false), based on some weird movements of money to Mrs. Reynolds’s husband (true). To show his innocence, Hamilton confessed the affair and Reynolds’s blackmail, privately, to James Monroe, giving Monroe copies of correspondence between him and the Reynoldses. That really meant confessing and giving the documentation to Jefferson and James Madison, who sat on it until 1796, when evidently they gave the documents to Callender and told him to fire away.

Callender did so—and operating on the “why not both” philosophy, alleged the financial corruption as well as the marital infidelity. As chronicled on stage and screen, Hamilton had to publicly confess to the affair in order to prove himself innocent of the corruption. He and Monroe almost fought a duel over it. But Aaron Burr stepped in to mediate, so everything turned out fine after all.

Such was the process by which the U.S. bludgeoned its way through its first contested election. The system that the founders, in their infinite dissociation wisdom, had come up with for the operations of what we now call the Electoral College made the runner-up the Vice President. Thus the bitter enemies Adams and Jefferson, now bitterer than ever, served the same new administration, with Jefferson, in the Republican minority, presiding over the Federalist-majority Senate. Things didn’t exactly go well.

Next time I post in this bad-election-history series—whenever that is—I’ll try to jump a century or two so we don’t get too bogged down in the origin stories. But we will at some point have to have a go at the 1800 election, when Adams and Jefferson competed again. That too was quite a scene.

________________

Further Reading

I don’t usually do further-reading links in these free, public posts—trying to make that a perk for my paying subscribers—but I did want to note that my ideas about Washington and presidential term limits are drawn from to-me fascinating and persuasive scholarship by B. G. Peabody. (Paywalled, sadly.)

Bad history is good history, IMHO.

These are great. You can stay with the origin stories.