This is the third in a three-part series on race and gender issues, more surprising than they might seem at first, in “cover” versions of recordings we tend to know better in the covers than in the originals. This one’s a public post.

The first two entries in the series were paying-subscriber exclusives. #1:

Historically Important Cover Songs

I don’t like covers. But whenever I say that, you start throwing a zillion examples at me of manifestly great covers, greater even than the originals, and the lists are of course endless: What about Hendrix’s “All Along the Watchtower,” Joplin’s “Bobby McGee,” etc., etc., etc.? . . . And the fact remains that except for a very few, I tend not to like anything on those lists, because they’re covers, and I don’t like covers.

. . .

And #2:

History-Making Cover Songs, Part 2 of 3

The last time I wrote about transformative popular-song covers—“Respect” and “Make Me an Angel”—I defined my various terms (or failed to define them!) and gave some music-business-history background, so I won’t do that here. That post, the first in a series of three, turned out to be about how two women, each in her own way, forever rein…

. . .

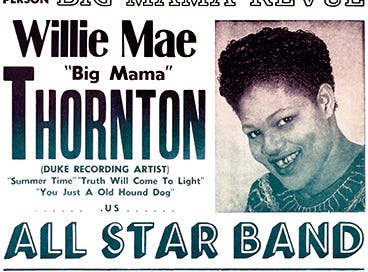

But I thought I’d do this one for everybody, and I was going to write about “That’s All Right, Mama,” which has a story more complicated than people know—I mean more complicated than “the black dude got ripped off,” though evidently he did—but I’ve decided to look instead at another Elvis Presley hit, “Hound Dog,” a cover of Willie Mae “Big Mama” Thornton’s “You Just [sic] an Old Hound Dog.”

For one thing, “Hound Dog” brings the male/female cover-song dynamic I wrote about in part one of the series together with the race matters I wrote about in part two. Also, I just remembered that it was my own process of sorting out the relationship of the original and the cover recordings of this particular song—the trial and error and getting it wrong—that helped shape the view of the history of American pop I have today.

Travel back with me, then, to my teens, when I knew who both Presley and Thornton were but didn’t really know their music. I’m way too young—younger than springtime—to have been a Presley fan when he broke out as a pop phenomenon. He released his first single when the fetus who became me wasn’t yet conceived, though it soon would be, and to say that my parents weren’t Presley fans would be putting it mildly. Rock and roll and r&b weren’t recognized in our house until they landed in my and my brothers’ teenybop tastes in the early-to-mid 1960’s, spearheaded on AM radio by the Beatles and the British Invasion and developed there by soul, and the rest is history, bad and good. (Much later, I was forced to realize that as teenagers in the ‘40’s, my parents of course heard r&b and what I, anyway, call rock and roll: what else are “A-Tisket, A-Tasket” and “Minnie the Moocher”? As adults, though, they didn’t play the pop of their youth.)

Everything I know about Elvis I therefore had to learn both in retrospect and in contradictory stages of assessment. First, I learned, vaguely, that he was a washed-up, always pretty square predecessor to the music I thought was cool. I had a grandfather who once referred to Elvis, when I was probably nine or ten, in a “these goddamn kids” kind of way, and I was like “who’s Elvis?”

Soon I learned that the Presley movies, as shown on TV, were unintentionally funny in a cringe-retro way. Also that as the oddball crooner on the 1969 single “In the Ghetto,” the guy seemed to be trying way too hard to be relevant.

Somewhere along the way I absorbed the fact that Presley had been the first rock-and-roll megastar, with the screaming girls and so forth, pre-Beatles. Then I ran into him in his late-career comeback as a not super-impressive country artist in the top-forty c&W radio format I’d gotten into. Then, having long since become a notably weird Vegas act, he died, and only slightly later, or maybe simultaneously, I decided that on his early recordings (especially, for us developing purists, the pre-RCA tracks on Sun Records), he’d been not only groundbreaking but great, helping invent aspects of the rootsy forms of pop a lot of us had taken up without really respecting their antecedents. In my early twenties, like a lot of nerds my age, I was listening closely to the Sun Sessions LP compilation—those tracks laid down when I wasn’t quite yet in utero.

And finally I’ve decided (because at this point I really don’t expect my view to change) that Elvis Presley’s legacy will on balance be a lot more durable if we remember him more as an astonishing theatrical force and agent and product of change than as a singer and musician whose whole recorded output we should pay close attention to. It doesn’t necessarily take anything away from him to say there’s a lot of better music out there than his. Some of the early recordings, and now I mean on RCA, remain irresistible in part because the relatively slick arrangements—compared to what some of us once prized as the stripped-down vibe of the Sun work—enhance the performer’s amazing talent for sheer expressive presence. Yes, I mean I actually think the Jordanaires’ backup singing on “Teddy Bear,” “Don’t Be Cruel,” and “Hound Dog,” for example, helped make Elvis more truly Elvis-like than he’d been at Sun.

More important, maybe, is the thing that jumps out of his singing as legitimate sexual intensity, combined with the sheer blatancy of the come-on. You can hear him shimmying just in the vocal, and it doesn’t matter what he’s singing about. The sexuality embraces what people used to call androgyny and have more sophisticated names for now. It’s the after-hours tent-show stripper thing, copped no doubt from women, as well as from gay, bisexual, and cross-dressing black performers like Little Richard and Esquerita. Suddenly that thing was put under the hot lights of television and broadcast into America’s prime-time living rooms for all to hear and see. White kids had been listening to—and white artists performing—black music for generations. Black and white musical traditions had been swapping with and mimicking one another ever since the first European and African presence in North America. Girls had screamed for Sinatra and for Al Jolson. Bill Haley and the Comets scored a national pop hit with “Rock around the Clock” when Presley was still only a regional act. Yet the Presley thing was new, for reasons of its own, including the advent of TV, the “baby-boom” mainstreaming of the teenybopper, and the large and consolidated amounts of showbiz money that started changing hands after WWII. And a lot of that had to do with sex.

Anyway, someday and somewhere I’ll explore why I think that in 1956, when I was one and Presley appeared for the first time on the Dorsey Brothers TV show, rock and roll—it’s identifiable in some of the earliest recordings of vernacular American music in the 1920’s, and was called by that name beginning in the late ‘40’s—came to an end. Today I’m on the track of something else.

For in my teens, I also had a sense of Big Mama Thornton, the first to record “Hound Dog.”

Though born nine years before Presley, Thornton released her first single in 1951, only three years before he released his. By 1969, when he released “In the Ghetto,” I had a clearer sense of her, or thought I did, than I had of Presley: her song “Ball and Chain”—Thornton both wrote and recorded it—was covered by Big Brother and the Holding Company, whose lead singer was Janis Joplin, on their breakout 1968 album “Cheap Thrills,” which was really her breakout album. Along with reaching number one on the Billboard album chart, “Cheap Thrills” was in my opinion at the time the greatest album that had ever been or ever would be produced, “Ball and Chain” its greatest track.

I now think the LP holds up incredibly well, especially “Ball and Chain (I just listened to it yet again, and I have better ears now). But the point, for this piece, is that because I stared for hours at the R. Crumb album cover, whose design rightly places “Ball and Chain” at the center—Crumb portrays Janis sweatily crossing a desert dragging a literal ball shackled to her leg by a chain—I learned, from a thought bubble above the ball, that the ball was thinking “by ‘Big Mama’ Thornton.”

Thus I deduced that Big Mama Thornton was one of the greats.

Did I therefore run out and search for Big Mama Thornton recordings? No, I did not. At that age, I wanted to be an aficionado more than I wanted to find music and listen to it. And back in them days, kids, if ya wanted to find older recordings, ya couldn’t just hit “search” on yer damn phone. You had to go out and actually search. That often still meant searching for scratched-up 45-rpm and even 78-rpm singles. By ‘69, some compilations and LP reissues were in fact coming out, and I think I got B. B. King’s classic 1965 album “Live at the Regal” from the Salvation Army, or maybe even at Korvette’s record department, but where a few other kids I knew—actual aficionados—did actively seek out older albums and singles, I was lazy. And with “Cheap Thrills” to listen to again and again, and again, why look elsewhere?

All I knew, that is, about Big Mama Thornton was what I imagined of her: a great old-time blues singer, I assumed; a black woman; probably fairly large. I no doubt got that it wasn’t her parents who named her Big Mama, but I didn’t know or care what her real first name was.

In real life, “Ball and Chain” wasn’t an old song. Janis was covering a later-career, non-charting Thornton single, released only the year before “Cheap Thrills” came out. Still, if the name came up in conversation, I was equipped to nod and say “Big Mama Thornton. Writer of ‘Ball and Chain.’”

Good enough for fourteen-year-old Bill.

Cut to sixteen-year-old Bill, in a long-distance relationship with and intermittently seeing a girl who was way ahead of me in connoisseurship, and in her case it was the real thing. When I was raving up the Jefferson Airplane and the Grateful Dead, this girl was listening to “Mingus Ah Um” and old Otis Redding and Ray Charles tracks. The only member of the standard FM-band AOR canon of the moment I recall her showing any interest in was the Band.

Anyway, in the fall of ‘71, having Greyhounded from Brooklyn to her parents’ big house in Cambridge, Mass., for a weekend visit, with leaves falling around Harvard like it’s the movie “Love Story,” which I’d laughed at for its obvious awfulness while secretly finding the location romantic, I didn’t know I was on the verge of falling into a long and true romance. In only a few months, I’d be holding my first five-string banjo, with no idea what to do with it. I was maybe six months out from first hearing Hank Williams. Maybe a year away from first hearing Memphis Minnie. By senior year of high school I had Jean Ritchie and Ornette Coleman in heavy rotation, and so on and so on into the whole great mess. . . .

But that fall, the romance hadn’t quite started yet. The relationship with the girl in Cambridge would be short-lived. But did I come away from it with a glimpse of—a listen to—a better way to approach music? Not sure.

What I think I remember is that during that weekend visit, we had a Big Mama Thornton LP on the turntable. I don’t know which album it was—Thornton worked right up to her death in 1984—but from the b&w photo of the artist on the cover, I took it to be old (anything pre-British Invasion looked old to me) and in that sense cool, esoteric, in-the-know, grown-up.

And the singer looked pretty much as I’d imagined. One of the tracks listed was “Hound Dog,” which I knew to be an old—“old”—Elvis Presley hit.

So I said: “Wait a minute. Big Mama Thornton—who, as I'm sure you know, composed ‘Ball and Chain’—did ‘Hound Dog’!?”

Or words to that effect. To which the answer was Yes. It was Big Mama’s song before it was Elvis’s.

And so with the autumn leaves falling outside, the girl and I shook our heads and laughed merrily—well, I did—about goofy Elvis copping such a deep, authentic, old blues number from a grownup roots artist like Big Mama Thornton, one of the greats, and turning it into such a slick, silly, teen-pop production in a mode by then so painfully outmoded. That’s the way I still regarded Presley’s work at the time, to the extent that I regarded it at all.

I should say that don’t remember getting much out of Thornton’s “Hound Dog,” or the album, at the time. I had other things on my mind that day, of course; still, given the fact that less than a year later I’d be hearing really good things in old Smithsonian field recordings of quavering, wavering white southern singers and the tinnily captured bottleneck guitar of black southern players, etc., it’s odd to me that “Hound Dog” came off, that day, kind of remote.

I didn’t have the ears. It’s a very strong recording—as is the original “Ball and Chain.” That’s important to me in part because the original recording of “That’s All Right, Mama,” by Arthur “Big Boy” Crudup, just isn’t all that great.

But instead of comparing Thornton’s originals to the Elvis and Janis covers—also very strong—there’s a much bigger fact to note about “Hound Dog.” It’s a fact I could never have processed at the time and didn't process at all for a long time afterward.

Thornton did write “Ball and Chain,” but “Hound Dog” was written by Jerry Lieber and Mike Stoller, well-known composers of classic teen-pop hits of the late ‘50’s and the ’60’s recorded by the Coasters, the Drifters, and others. The Lieber & Stoller partnership, reliably turning out big youth-culture numbers with an r&b feel, remains one of the great successes of the commercial arrangement known as “the Brill Building.” Some of the best American vernacular music was made that way.

“Hound Dog,” that is, never was a “deep, authentic, old blues number,” whatever that was supposed to mean, emerging from a world unknown to teenybop pop. It was a song written especially for Thornton, in about twelve minutes, at the home of Johnny Otis, a black bandleader and record producer, by a pair of Jewish teenagers, one from Queens, the other from Baltimore.

That puts “Hound Dog” right in the lineage of “Love Sick Blues,” and it tells us a lot about about the historical and racial, ethnic, and financial realities of American show business, roots music, rock and roll, and much else. Something too about the nature of the creative process. And yet for years, that story would have been, for me, unaccountable. In fact, I think I saw “Hound Dog” attributed to Lieber & Stoller more than once, and just said “nah” and looked away. The reality is a million times cooler than my old dreams about a rootsy authenticity where, in my youthful purism, I somehow managed to mentally segregate—I’m sorry to say that’s the mot juste—the music of the Willie Mae Thorntons of the world, whom I idealized, from the music of the Lieber and Stollers of the world, whom I had the almost incredible temerity to look down on.

It’s just more interesting to me, now, to know that when Elvis Presley covered “Hound Dog,” he wasn’t recording, for the pop charts, only a hit from the r&b charts—that’s what “cover” used to mean—but also a song written by young, white professional composers paid by a black producer to channel the raunchy, fed-up irritation of a mature black woman. And I’ll close my “covers” series there.

FYI: There’s all kinds of good info about composing and recording Thornton’s “Hound Dog”: where the Latin rhythm came from; the sexual content of the original version (scrubbed from Presley’s); what it was like for Lieber and Stoller to meet and work with Thornton (amazingly to me, they’d already written r&b hits for Big Joe Turner, Charles Brown, and Little Willie Littlefield); and more. You can look it all up on the Wikipedia.