TEMPORARILY UNLOCKED

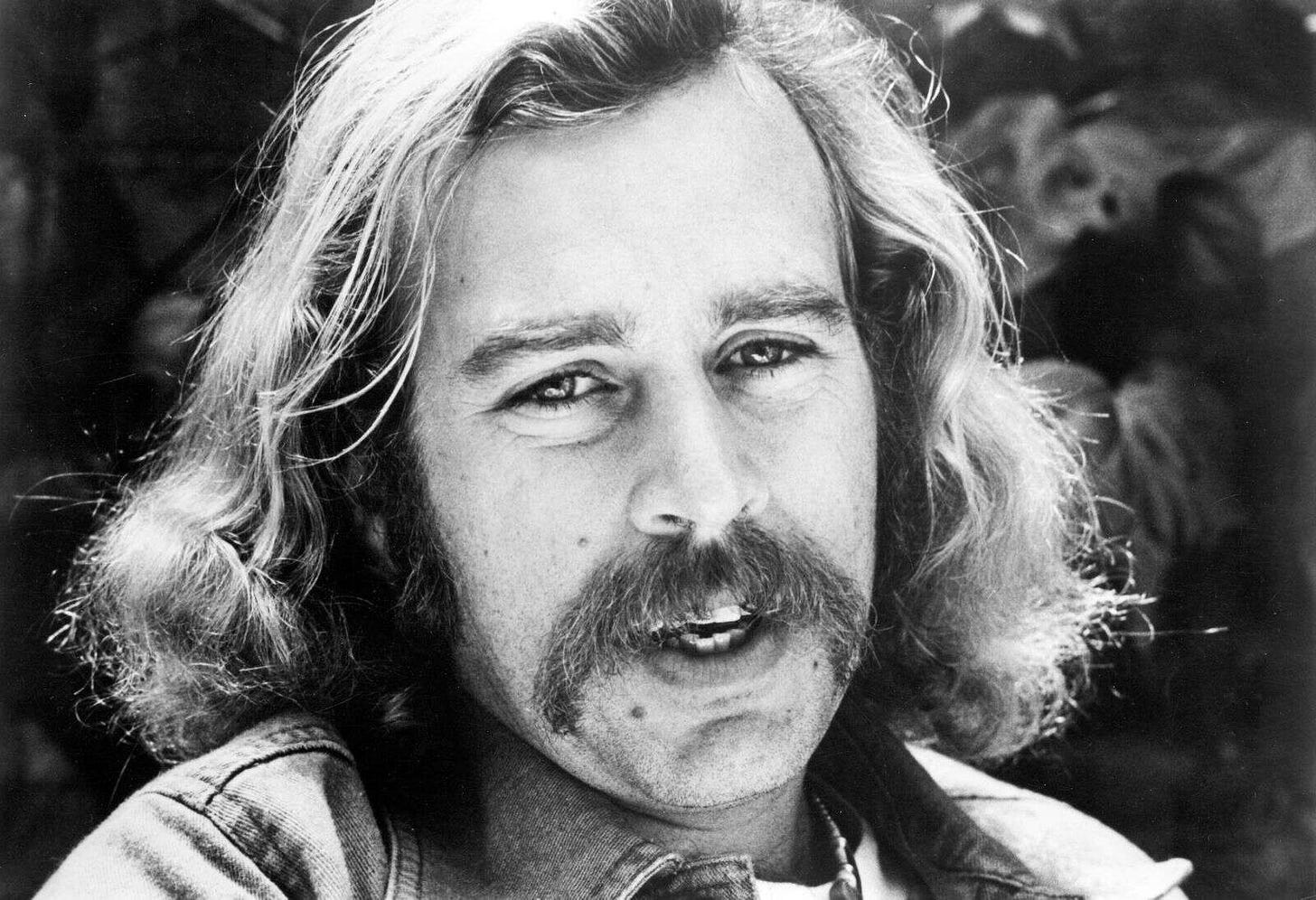

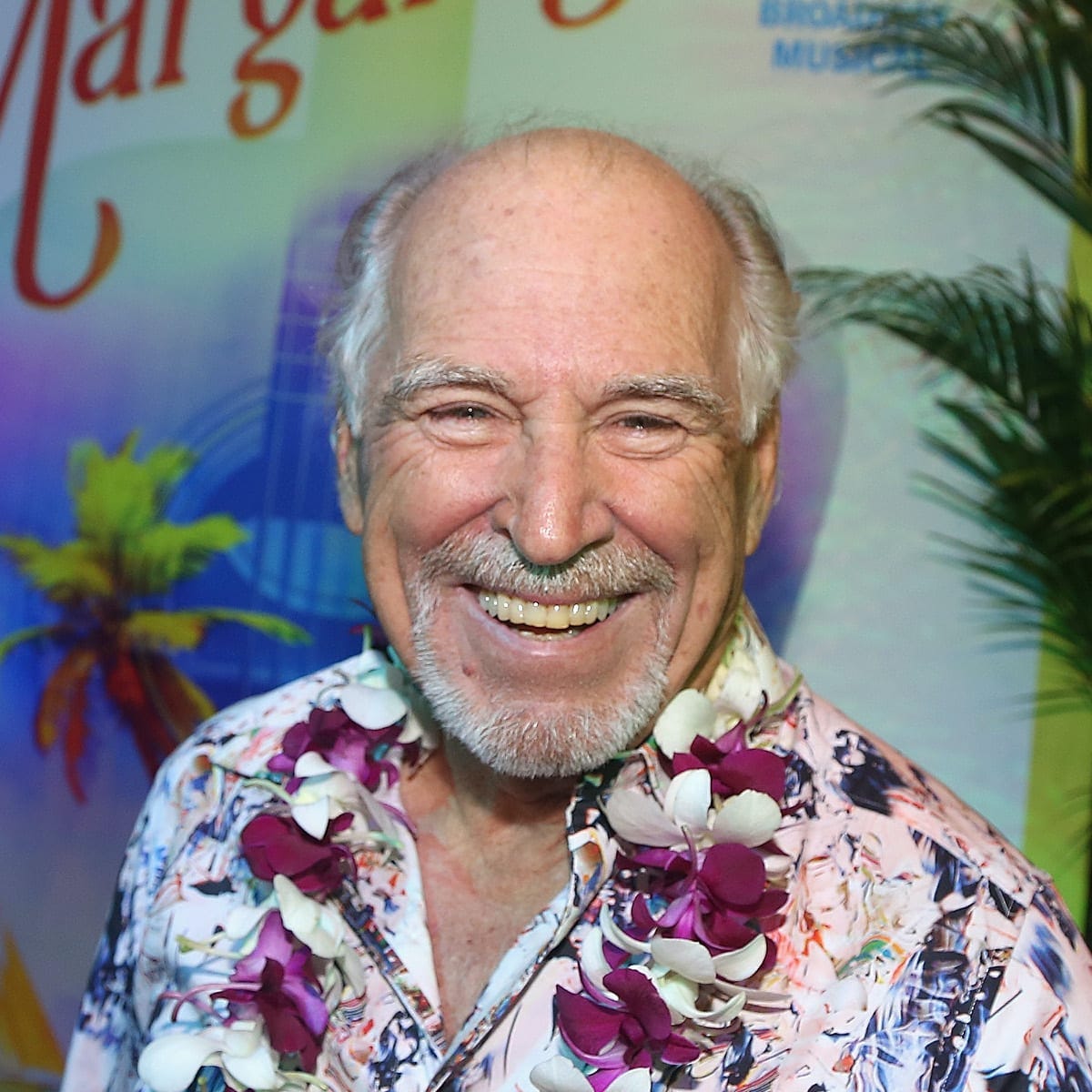

I was reading a New Yorker article by Nick Paumgarten on the “Margaritaville” retirement-community chain, developed by the singer-songwriter, author, and entrepreneur Jimmy Buffett and named for his most famous recording, a top-ten hit released in 1977, when Buffett and his audience were thinking about retirement, if at all, only in the most abstract way and the salient characteristics of the generation called “boomers” now retiring, had yet to be defined.

There are some fascinating things in the article, for me, anyway. I knew Buffett’s early work, beyond the hits, fairly well back in the late ‘70’s and early ‘80’s, and I still think it’s underrated. I’ve also watched from a bemused distance as, ever since, he’s been building a vegged-out tropical-vacation fantasy vibe with evident appeal for a large number of white “boomer” types (people in their fifties are also living enthusiastically in Margaritaville community). The vibe comes complete with merchandising, new product development, new recordings by the creator that seem designed solely intended to support the brand, a fangroup identification as “parrotheads,” and lifestyle experiences that take the long, strange Buffet-fan trip to an obvious and in every sense ultimate conclusion: retirement, the end of the road.

I think the article reads a number of things about Buffett’s early career quite weirdly, even flat-out wrong. I won’t go into them in detail here. Some arise inevitably from the oh-so-knowing New Yorker culture-reporting style, always going for a too-tight summation, almost always missing. “A poor man’s Gordon Lightfoot” might sound both informed and clever to a reader who hasn’t actually listened to some of the work and just wants to get situated comfortably by a supposed authority. It’s no weirder to me that Bob Dylan has praised Buffet’s songwriting (he has) than that he’s praised Lightfoot’s (same interview). When you’re breezing along typing—seeming to, anyway—not all the presumptions that come flying from your fingers onto the screen are going to hold up.

But the big misunderstanding isn’t Paumgarten’s or The New Yorker’s alone. It’s general, and it’s about “Margaritaville”—the song, not the retirement community. What’s really bonkers is that the totality of this misunderstanding is critical to the overwhelming success of the Buffett brand. Far from a hymn to vapid, good-time relaxation, “Margaritaville” is about a young man sunk in a deep, though not totally dissociated depression.

It’s a good song. Overly familiar now, putting it mildly—I can’t stand listening to it, but then I can’t listen to “Brown-Eyed Girl” for the zillionth time either— “Margaritaville” was unusual when it came out. I first heard it on top-forty country radio when a certain kind of folky soft-rock pop was crossing so far over into country that John Denver won Best Entertainer at the Country Music Association Awards in 1975. (Charlie Rich’s angrily protesting that award was kind of funny—who in country was more pop than Rich? Seemed like a turf war, L.A. vs. Nashville, not an genre-authenticity war.) But even amid all the songs oozing into country from the easy-listening charts, Buffett’s song stood out, and less for its faintly Caribbean lilt than for the kind of story it told, and told deftly and wittily, and of course pretty slickly: good rhymes, three evocative verses, and a chorus whose tagline shifts as it tracks the narrator’s slow-dawning, highly provisional beginnings of self-recognition.

Here’s a perpetually drunk young man in flight from something, dedicated to wasting away, as he puts it, somewhere tropical, with no clear idea why. He’s not down and out. He’s secured himself a place with a front porch. He has a guitar to strum. He has a kitchen where he can boil shrimp. And he has alcohol blackouts.

This heavy-drinking theme distinguishes the narrator somewhat, but the image itself wasn’t all that original. He’s a late-1970’s, post-hippie development of what had been known since the 19th century as the beachcomber. The 20th century had its surf-bum dropout variant; I think of the Big Kahuna in “Gidget” (1959), which I watched on TV as a kid in the late '60's, goofing on it but secretly dreaming not about Gidget but about how cool it would be to be living on the beach and totally free like the Kahuna. (“Seventeen-year-old girls want him! Fourteen-year-old boys want to be him!”) The Kahuna’s pain, whatever it was, was getting worked out, or not worked out, less by self-immolating drinking than by having a rep for womanizing. While he was leader of an adoring gang of much younger surfers, the main thing about the Kahuna was being rootless, and being alone.

Our Buffett guy is alone too, existentially anyway—neither we nor he know what goes on during those blackouts, though one resulted in a tattoo. The absolute dead-end nature of his current choice of existence is borne out in the song’s immediate plot, which features exactly one event: when his flipflop breaks, he cuts his heel on a beercan poptop and goes home, bleeding and looking for more alcohol. If this thing weren’t all tropically rhymey and swinging, it would be Bukowski.

The real movement in the song comes in the shifting tagline in the chorus. This wasteaway knows he’s a type. There are other dropout men like him. Some of them tend to blame their sorry state on a woman, but he starts out seemingly more enlightened than they are: his thing is to blame nobody. That might seem generous, even-handed and even anti-sexist, but really it just reflects his overall passivity.

By the end of the song, he’s realized that there actually is somebody to blame. It’s him.

Nothing follows from that, which is good songwriting, because we get to wonder, or even decide, whether he’ll now start getting his shit together or has decided to embrace a spiraling descent into the void. Either way, an oddly mature and thoughtful, even somewhat tough-minded sensibility has come into play.

Odd in 1977 male songwriting anyway. The only thing like it that comes to my mind right now is Dylan’s “Idiot Wind” (1975)—and now I’m wondering if “Idiot Wind” was an influence on Buffett. The chorus tagline works just the same way, though it moves in Dylan’s case from howling excoriation and blame to some grudging degree of shared responsibility.

Hm.

It’s not that “Margaritaville” doesn’t romanticize its downward-spiraling wastrel of a hero-bum, especially his sense of self-blame. Of course it does. Otherwise it wouldn’t be a song, and a song that I, at 22, was bound to like. Romanticizing that kind of stuff is what Romanticism once was. It’s not clear to me that there’s some categorical difference between Shelley in Tuscany and Buffett in Key West. As the Big Kahuna tells Gidget, about another surfer: “That's Lord Byron. The beard means he digs existentialism.” So I get the appeal—oh, do I ever—but what comes to mind now, when reading about the branded retirement communities, is that back in ‘77, I thought the appeal had to do with a reasonably smart artistic blend, unusual in lightweight pop: the narrator’s critical angle on the situation and self-destructive seduction of the situation itself.

That’s not what the fans got out of it, though, and the rest is weird American branding history. It’s tempting to think Buffett was like, “OK, fine. If you don’t appreciate my ability to blend a singalong with relative psychological and emotional sophistication—relative to, say, Gordon Lightfoot—then pay me lots of money for dumb stuff, you biggest and most prosperous generation, that works too.” It’s been widely noted that Buffett, an inveterate hustler, by no means lives the Jimmy Buffett lifestyle, but I really don’t think you can sustain a brand as successful as his on mere cynicism. An entire subculture, celebrating a certain idea of Eros, has been founded on a one-off hit song from almost fifty years ago exploring a certain idea of Thanatos. That irony reaches its height in opening retirement communities. The next step, from places like that: death itself.

I can’t explain the Buffett phenomenon. Maybe Buffett can. When the main character in Malcolm Lowry’s novel Under the Volcano wants to blackout himself to death in the tropics, he slams straight mezcal. When Nicholas Cage wants to blackout himself to death in Las Vegas, he stocks up on every kind of hard booze. But the guy in Buffet’s song is wasting away on . . . blender drinks?

It’s the Death Wish, all right. But it’s Death Wish Lite, and I guess that’s a white-America fantasia you can’t go broke catering to.

______________

Further Reading

A Buffett song that Dylan likes.

Dylan’s done this one in concert, but I like the original: “A Pirate Looks at Forty.”

The man had a wit, a way with an unpretentious rhyme, and he could catch a mood: “The Great Filling Station Holdup.”