Democracy in America?

The current crisis might remind us just how hard it’s been to get democracy going here at all.

Evidence presented by the Jan. 6 select committee of the House of Representatives has exposed an all-out, multifaceted, grotesquely blatant effort by former president Trump to overturn the legitimate outcome of the 2020 presidential election and remain in office illegally, subverting not only the will of the voters in that particular election but also the entire electoral process by which presidents hold office in this country. It’s thus been widely and justly noted that his effort was an assault on American democracy itself.

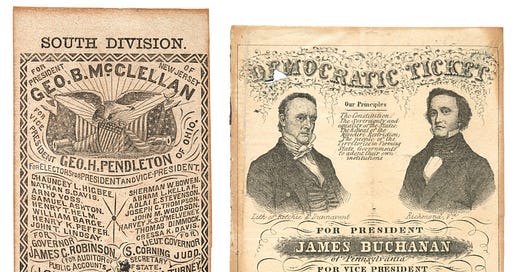

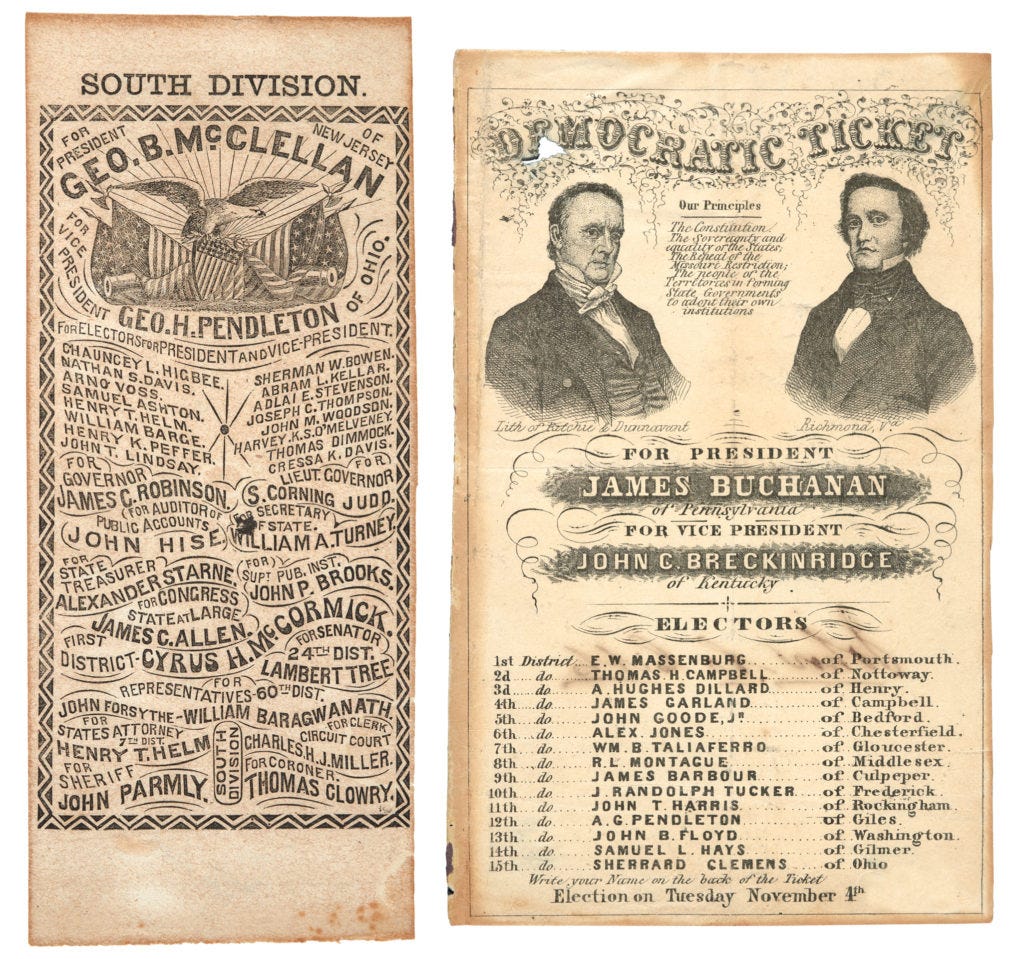

One of the mechanisms Trump used in that effort is what we call the Electoral College: the system unique to presidential elections, where voters are really choosing not their preferred candidate but a slate of electors committed to the candidate. Each state gets a certain number of electors, proportionally to its population; in most states nowadays, the candidate who receives the most votes in the balloting process wins all of the states’ electoral votes.

Much of Trump’s assault on American democracy, from trying to get states to name “alternate” electors to pressuring the vice president to refuse to certify the electoral-vote tally, emerged from his criminal cohort’s identifying opportunities for inserting partisan chicanery into the minutiae of the state-by-state logistical workings of the Electoral College and thus defeating its normal process.

But the normal process of the Electoral College is undemocratic too. Only via that institution was Trump elected, against the wishes of most voters, in 2016. Our presidential election system subverts the popular will—but legally.

Other well-known American governing practices and institutions are equally undemocratic. The anti-majoritarian nature of the filibuster in the Senate is getting a lot of attention right now, but the Senate itself is thoroughly undemocratic: each state, regardless of population, sends two senators, a system that defeats, in a house of the national legislature, representation of the national majority. The current Supreme Court seems to be on the verge of overturning Roe vs. Wade, and it’s been handing down a raft of other decisions contrary to most Americans’ preferences. The appointment of justices and the Court’s operations are anything but democratic.

And that’s all by design.

Hence a problem for talking about American democracy in the midst of the current crisis of attack on the Constitution—a problem, more importantly, for doing something about maintaining democracy.

The American people have made an amazing effort, over many long struggles, to transform inherently undemocratic institutions into agents of democracy—to subvert, in a way, the intentions of our founders. But having bent the institutions out of shape, we can find them all too easily snapping back into something like their original forms. And because we have to defend what are in fact quite undemocratic constitutional processes against the flat-out criminality and tyranny of Trumpist corruption, we can get confused and frustrated by the very nature of the democracy we’re so desperate to preserve.

The problem began, not surprisingly, in 1787. The men who argued amongst themselves, that hot Philadelphia summer, over creating a national government weren’t just undemocratic or, as often said, leery of too much democracy. They were avowedly anti-democratic. During and after the war, popular plans for economic equality, making major inroads, had given the upscale good reason for fear. For all of their many differences, suppressing democracy was what got the delegates to Philly.

They argued about everything else. Not about that.

So even in its early proposed forms, the Senate was to be a very small upper chamber, not elected by or representative of voters; its purpose was to put a strong check on the lower chamber, the House of Representatives, which was to be elected. Many people today—people like me—don’t like the Senate, because it’s unrepresentative of the whole people, but it was never supposed to be representative of any people—not even the people of the states. The state governments were represented in the Senate, so the states’ legislatures, not the states’ voters, chose the senators. We didn’t start voting for our senators, per a constitutional amendment, until 1913.

(Sidebar, with more to come another time. The fact that Madison and Hamilton, for two, hated the states’ “equal suffrage” in the Senate and involvement in the Electoral College didn’t make them pro-democracy. They wanted to vitiate the states’ power on every front, because it was the states’ weakness that had been encouraging and enabling ordinary people’s democratic economic efforts, which Madison and Hamilton wanted to suppress. Both of them wanted a smaller, less- or un-representative upper house to check the lower, but they didn’t want the states represented there. They lost on the second part of that deal. We live today with the cognitive dissonance reflected by the Philadelphia convention’s trying to combine a kind of House of Lords check on a lower house with a house that also represents the state legislatures.

Just one more bad, cobbled-together compromise, with results that are wack.)

But the House, too, was to be small, with big districts, representative only in a pretty limited sense. And ideas floated for electing the executive branch by the House were shot down fast. Separating executive power from the representative branch had the purpose of insulating that power from popular influence; the executive was to be elected separately, but not, again, directly by voters nationwide but by that crew of prominent electors, chosen by the states, in whatever way they wanted, which in those days might involve popular elections or might not, known today as the Electoral College.

Regarding voting in the founding period overall, it's important to remember that racist, sexist, and classist election laws already made elections wildly antidemocratic—in most states, unrepresentative even of the majority of free white men. But it’s just as important to remember that an individual right to vote was never contemplated by the founders’ Constitution anyway, for anybody, even white male elites. The system called federalism, that is, was antidemocratic too. No universal rights and privileges were constitutionally protected for citizens of the United States, except against the national government, via enumerations in the first ten amendments. Your state remained free to restrict your speech, freedom of religion, voting, etc. Your being taxable by the federal government under the Constitution didn’t make you a national citizen with immunities, uniformly shared by all Americans, against your state. And nobody ever heard of a nationally protected right to vote.

Now they have. Given the realities of the founding situation, the bumpy, messy, struggling way we got so comparatively democratic, without actually throwing out the founders’ Constitution and starting from scratch, is a story in itself.

Today, though, I’m only noting how stuck we are with a lot of the old, antidemocratic national operations that the founders gave us, enabling government action against the interests of the ordinary American majority, not just outright criminal action, like that of Trump, but also perfectly legal action by both majorities and minorities in Congress, by federal judges all the way up the line, by presidents, by state legislatures, by governors, by boards of election.

We do have to defend our basic institutions from criminal attacks by Trumpists, who are, indeed, not only attacking the elitist republican systems created by our founders but also attacking the modern American democracy we’ve made from those systems. What we’ve come to rely on as modern American democracy, though, doesn’t inhere in those institutions. Major forces, both legal and illegal, seem to be trying to push them back toward original intent.

Bravo, Bill. You take on the public's misunderstanding of what "democracy" meant when the Framers successfully prevented it in the Constitution, a misunderstanding that makes it extraordinarily hard to explain to the public what "democracy" means now, and why what the public thinks is "our Democracy" is not what we have. Since full democracy is now unconstitutional, blocked by what's left of the Framers' legacy, it will be extraordinarily hard for us to get it. My hope is that the old Right-wing view that a "republic is not a democracy" will not recur; and that it won't require civil war, as it did in the 1860s, to get the Constitution amended to make it more democratic.

Timely piece Bill, and I’m firmly in the camp of admiring like you the ability of our nation to prosper and adapt to the compromise laden founding document. As well, the unique and unproven nature of our founding based on the socio/cultural/political realities of the age was not destined to succeed as many of that time assumed, hoped or feared. I’m amazed that we have lasted this far, and perhaps it was Providence indeed that cast its gaze in our experiment and willed it to succeed in spite of its peculiar founding.