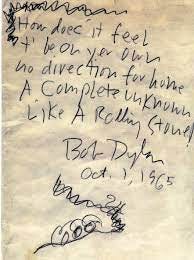

“princess on the steeple and all the pretty people drinking thinking that they got it made”

The following is just an experiment.

Background: I’ve deleted all of my tweets, from the first time I ever posted on Twitter, on April 4, 2010, through the last of the three I posted on January 23, 2021.

I would like to have left some of the goofiest tweets up (when I said “Blazing Saddles” is objectively not funny, the replies were funny), but it seemed too complicated and tedious to pick and choose, so I dumped the whole oddball raft of work that I’d posted during the almost eleven years that ended late this January. I’d already gotten fed up with doing the long-thread “Twitter essay.” Moving away from that is one of the reasons I founded HOGELAND’S BAD HISTORY and started posting regularly here, in something at least approaching real essay-like form, with actual sentences, paragraphs, transitions, etc. Back to my roots.

But before I deleted the tweets, I downloaded them. Then I wondered what you’d get if you were to break out a thread and set it up as if the tweets might (or might not) form a real essay. In that spirit, below are three bursts from last summer, arranged in the form of normal prose, inspired by the launch of the magazine “Persuasion.”

The following are off-the-top-of-the-head, strung-together tweetbursts on the ongoing free speech debate, now trying to pass as sentences and paragraphs.The context was this notion: “woke” discourse has so infringed the speech of people previously well published, and whose views are now not approved by that discourse, that they've had to flee to new spaces.

Burst #1: Welcome to My World

If the definition of being censored and having one's freedom of speech violated has drifted into not being easily able to get a mainstream hearing, thanks to prevailing vogues, then I have a MAJOR CASE TO BRING, CALL THE DAMN ACLU!

WELCOME TO MY WORLD, FREE-SPEECH SNOWFLAKES!

Putting it bit more thoughtfully: As one whose ideas and approaches have only rarely been, shall we say, public-broadcasting ready, I’ve spent a long time coping with obstacles that some widely heard voices now seem offended by possibly having to encounter.

It's like certain well-published liberals, using the term broadly to include conservatives, have never even considered the old Marxist idea that freedom of speech doesn't mean much if you don't own the printing press. I do enormously appreciate legal protections for speech, despite the obstacles to wide exposure that blowing against prevailing winds and creating my own systems have caused me—I think free speech does matter, even when you don't get access to the printing press. And I don't think your free speech is violated when prevailing vogues make your speech unattractive to the corporate purveyors of speech. But the Marxists have a point. I now begin to think some people believed they were getting widely published for some reason other than the alignment of their speech with certain approved moods.

Princess on the steeple….

A word of caution, then, from the mouth of an old horse:

A lot of writers bemoaning the supposed end of free speech are only startled by a fear that they're not going to have it so easy any more. And there are those who haven't even been widely published, yet still aspire to the platforms that the big-timers enjoy, and imagine getting there someday. These people are upset and offended on behalf of something they've been left out of! The Marxists call that false consciousness.

In other words, while I doubt there's anything I'd want to write that the new magazine Persuasion would want to publish, that doesn't mean I think Persuasion is censoring me.

Burst #2: Fun

Further on this thing where unpopular ideas don't get a big hearing, and whether that's a free-speech issue:

People who have had access to big platforms, and fear access will now be harder, should realize they got that hearing because their ideas fit into a spectrum of acceptability. And realize that a spectrum of acceptability cuts other ideas out. By definition.

Based on personal experience, my reading is that you can say, in the New York Times, for example, that the US was founded on certain ideals. Depending on when you live, you can say that those ideals made us great, or that they they've never been lived up, to or that they're lies. Times change. Pun semi-intended.

But it's not just the Times. It's public broadcasting and what have you. Over time, it's entered the realm of acceptability to take a range of views about those founding ideals, and the older rah-rah angle has become less acceptable. What's acceptable and popular changes, and if it weren't popular and acceptable it wouldn't be in the Times.

That's just the deal. Some writers who have lived their lives ringing whatever changes on the popular ideas, and even writers who want to do that and haven't gotten to do it yet, are bound to get worried if the popular ideas change. Other writers of fundamentally the same kind are going to get excited, because their ideas are suddenly popular and will get a hearing that they would have been denied when other ideas were popular.

But if, on the other hand, you want to suggest that the country wasn't founded on those ideals at all, and maybe not on any of the aspirations people today invoke critically and otherwise when talking about the founding, times don't change. That is my experience. It's not that there's literally no place for me to go, happily, but there's no way, just practically speaking, that the systems I create for understanding the things I look at can map to big, powerful platforms.

I've gotten used to this. If you write in opposition to the entire system of popularity in ideas, to consensus, you have no reason to be upset when that system barely knows you exist. You need to be grateful for the places you do get to be—and grateful your freedom of speech is protected!—and just keep on keeping on.

(In the end, this stuff is supposed to be … fun.)

But most of those who fear being "silenced" because corporate media no longer find their ideas popular do have nowhere to go, spiritually, existentially: they never had an opportunity to question the validity of the system that's now turned on them. The public consensus on US history used to belong to one group. Let's oversimplify madly and call it Wilentz. Now it belongs to another group. Same qualification, let's call it Hannah-Jones. Some members of the old consensus, not just on history but on the nature and style of public discourse, may now feel SoL.

I'm against consensus. So in one way I've always been SoL. But in another way, I've been incredibly lucky!

Burst #3: Russia Today

A briefer report, this time, from the land of having ideas that just don't fit with, let's oversimplify, the public broadcasting view of US history and its current political ramifications at any given time.

Anecdotally, I can say there are frustrations. Back when Russia Today TV was reaching out to anyone expressing criticism of the US, and inviting them on shows to be admiringly interviewed the way, say, Jon Meacham is interviewed by the mainstream, they approached me more than once. This was well before the Trump election. A bunch of legit progressives were going on RT to be interviewed.

I get it, because when you're boxed out of the mainstream, it's frustrating. It's like Jon Meacham gets the Pulitzer, where can I get my prize: the gut thing is no more elevated or edifying than that.

So, well before 2O16, when RT came a-knockin' it was tempting.

But, you know, it’s state-owned, and in Russia they suppress speech legally as a matter of principle. I know, I know: we have Fox News, and the networks are corporate tools and blah blah. Still.

And when these free-speech people who think they're being silenced, because it's harder to hear them than it was before, get the call from the next Alex Jones, or from Tucker Carlson, will they take it? Some will. I think it's better to make a virtue of necessity and cultivate your garden. But then I have one to cultivate.

Anyway, I chose to say no to RT. Few had even heard of them then, and I had to invent a basis for that decision. I didn't have a basis. And then I did. So that's been OK.

THE END

[Hello. I’m back. I think the effect of the experiment is rather strange. At some point, though, I might try it again anyway.]