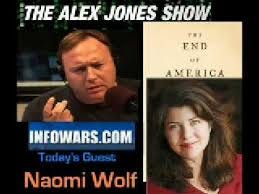

The author and public intellectual Naomi Wolf recently appeared on the right-winger Tucker Carlson’s Fox News show—she was billed as a representative of Democratic Party progressivism—to inveigh against what she and Carlson call a scheme to bring totalitarian dictatorship to the United States via government COVID policies. Their claim that the pandemic is a pretext for a fascist shift rang a bell with me, because nearly ten years ago, Wolf was on the radio with the right-wing broadcaster Alex Jones, sounding the same kind of alarm over the same kind of imminent takeover, though under different pretexts.

Some observers have been wondering how Wolf could have made what seems an abrupt switch to the anti-Biden narratives of Carlson and Fox. For background, I paste below something I wrote about her efforts way back in 2012, which was (wisely) cut out of a longish essay I published that year in Boston Review. Strangely enough, perhaps, the excerpt has mainly to do with Wolf's views of the U.S. founding, which is what I was writing about it at the time.

A lot of what's below feels strange to me now, looking back through Trump. Alex Jones and “Russia Today” (RT America) are better known now than when I wrote this, and hey, how about that George W. Bush administration, that Tea Party movement, that Occupy Wall Street?

The mystic chords of memory…

Anyway, adapted from a deleted section on Naomi Wolf and the American founding, from 2012:

"I would remind you that extremism in defense of liberty is no vice," said Senator Barry Goldwater, the great 1960's movement conservative, and Naomi Wolf would agree. The author of a number of well-regarded books taking strong feminist positions, and a former consultant to the Democratic presidential candidate Al Gore, Wolf has now joined people like Alex Jones, a fringe-right talk-radio host, Ron Paul, the hyper-libertarian member of the House, and many of the members of the Tea Party movement in embracing what she calls, in her most recent book, "absolute liberty."

In that book, Give Me Liberty, and a companion manifesto, The End of America, Wolf calls for a popular uprising against American authoritarianism—against, indeed, a "fascist shift," which she identifies with the administration of George W. Bush, though it should be noted that since the books were published, she’s extended her critique to the Obama administration too. And Wolf has forthrightly said she’s making "a conservative argument."

Some have been calling her a conspiracy theorist. She’s lent credence to the label by promoting her new point of view on Jones's radio show "Infowars." A compelling and unsettling Texan, Jones passionately objected, during the Bush years, to executive-branch overreaching; plenty of liberals have vocally opposed such overreaching too, so there might seem to be common cause, but Jones’s on-air rants glide seamlessly from criticizing violations of civil liberties to stating that the Clinton-accuser Paula Jones was a CIA sex slave and that the Bushes, Windsors, and other famous families are descended from shape-shifting giant reptiles.

He has a fascinating act. It’s clearly intended to have no intellectual credibility.

Why would anyone hoping to be taken seriously go on Jones’s show? A partial answer may have to do with the paucity of public outlets for really strong dissent. NPR is just not going to take up the not-uninteresting question of whether certain executive-branch policies may reflect at least some degree of authoritarian shift, so it’s possible to see certain public intellectuals as driven to the fringes by the banality and denialism of the center. Credible left figures have even shown up lately on Russia’s US-based, anti-American TV channel, RT America.

As Wolf herself demonstrates, however, there’s no cogent argument to be made when you’re collaborating with the giant-reptile spotters. The fantastical nature of Wolf’s clarion call for absolute liberty as an American birthright is exposed by her comically blinkered view of the U.S. founding.

She has a classic case of late-convert enthusiasm. We "haven't been taught," she tells us, just how patriotic, high-minded, prescient, and self-sacrificing the founding fathers were. Some might feel we have been taught that, to a fault, but because the founders and their virtues are new to Wolf, she’s sure they must be new to everybody else and she’s bursting to enlighten us.

With every move, she stumbles over reality. She says, for example, that both Thomas Jefferson and John Adams "longed to be left in peace . . . but both stepped up, again and again, to aid the nation when called to, very much against their personal inclinations, because they understood the status of 'being an American' existentially, that it means that one has signed on to fight the permanent revolution." That awkwardly loping move toward a foregone conclusion takes at face value the fashionable eighteenth-century notion that pursuit of public leadership should always be “very much against” personal inclination. While it’s true that Jefferson and Adams were beset by mental and physical misery, in both public and private lives, and sometimes bitterly resented obligation, it's a truism even among the most glowingly pro-founder historians that an intense ambition for fame—in eighteenth-century terms, lasting recognition for public virtue—motivated almost all of the famous founders. Adams is unusual for admitting it, at least to his diary.

Wolf’s pronunciamento on Jefferson and Adams is weird in another way too. She baldly characterizes those two founders as committing themselves—and all who have “the status of ‘being American’”— to a kind of Maoist permanent revolution. While Jefferson’s occasionally overheated rhetoric might be cited in support of that picture, it flies in the face of Adams’s famous assertion that he had to study politics and war so his sons could study math, science, and business, so their sons could study painting, poetry, music, and porcelain. (Yes, porcelain.) From warrior to bourgeois to aesthete in three generations doesn’t sound like the permanent revolution Wolf has in mind.

It’s no surprise, therefore, that Wolf can’t deal with Adams's presidency at all. In Give Me Liberty, she notes in passing that “John Adams was never comfortable with true citizen democracy,” an admission that must rank among the great understatements. Adams was of course explicitly opposed to broad democracy in voting; when it comes to liberty, his administration and his party pursued and established the Alien & Sedition Acts. Wolf explains those acts away as a momentary lapse in the absolute-liberty ethos that she insists was nevertheless fully embraced by all of the founders. There have been times, she has to admit, when “our commitment to freedom has faltered.” Such abstract phrasing softens the stark fact that the Alien & Sedition Acts represent authoritarian tendencies just as fully worked into founding-era politics as the commitment to liberty Wolf wants to emphasize above all else—and just as fully authoritarian as Bush administration policies today.

Wolf often deploys thrilling quotations way out of political context. A typical example comes from The End of America, where she quotes Alexander Hamilton’s condemning arbitrary prosecutions, convictions, and punishments. Wolf presents that position as a radical break with tradition fearlessly embraced by a young revolutionary, but Hamilton was really only parroting what by his time amounted to the most banal of Whiggish buzzwords: as early as the 1750's, Benjamin Franklin was noting that such language had become vacuous, because people on opposing political sides used it reflexively. In real life, Hamilton had no compunction about making use of arbitrary prosecutions, convictions, and punishments. Wolf’s ascribing a credo of absolute liberty to Hamilton, of all people, would have annoyed the man himself.

She also quotes the historian Gordon Wood on his famous idea that ordinary people during the Revolutionary period moved from deference to self-respect. In the process, she acknowledges that “certainly many elite members of the founding generation had fears and apprehensions about what this might mean,” and yet, she says, “the current of this powerful idea, reaching as it did into farms, towns, and villages throughout the colonies, swept history forward nonetheless." Waved away in that rendering is the turbulent contest between populist and elitist Americans over economic equality that actually marked the period. It’s a contest with relevance for the Occupy Wall Street movement, which Wolf herself has recently embraced. But class conflict over financial issues doesn't fit her picture of a founding America univocal against tyranny, so she can't explore it.

Ignoring such complexities leads Wolf to some strange recommendations for government today. She embraces, for example, referendum-driven direct democracy. Her founding heroes, to a man, recoiled from that approach.

She also envisions a newly progressive role for “states rights,” the ethos in which liberty is supposedly best preserved by locating power not in the national government but in the state legislatures. In taking up this idea, Wolf expresses blithe confidence that any anti-progressive laws popularly introduced in the states would be sure to “drive a countermovement” to "self-correct." All we have to do is “trust the American people.” A more skeptical view, both of the founding and of recent history, suggests otherwise. Modern referendums have notoriously given electoral success to anti-tax, anti-welfare, anti-marriage-equiality, and anti-immigrant provisions; “states rights” remains alive and well as code for racial oppression. The liberties of racial, religious, and ethnic minorities, of women, and of the economically unprivileged—the sort of people the founders bent every effort to keeping out of government—have never been achieved by defining liberty in Wolf's absolutist terms.

In 1957, President Eisenhower put 101st Airborne Paratroopers of the U.S. Army in the streets of Little Rock, Arkansas, with fixed bayonets, to enforce federal civil-rights law from local states-rights opinion. Wolf’s right-wing allies still see that moment as an assertion of an oppressive police state by which the liberties of white citizens of Little Rock and the state of Arkansas itself were dictatorially violated—just what Wolf now calls a “fascist shift.” Politics makes strange bedfellows, and Wolf seems to have no idea who hers are.

From the moment the country was founded, liberty and equality have been in a struggle, sometimes an explosive one. There are important criticisms to be made of serious violations by the current executive branch. Such criticisms can only be undermined by casting the historical drama of the American founding in Wolf’s obliviously romantic, even religious terms. Refusing to entertain any of the thorny ironies of our national history, Wolf makes her call to action a call to nothing.

I’d only add, in 2021, that Wolf’s fantastical brand of good-vs.-evil conspiracism matters more now, when there’s even more actual surveillance, data collection, and intrusion by government and others. If there a shadowy world government really exists, really dedicated to turning us into placid robots, Wolf must be one of its undercover agents. Her assignment: to replicate our real concerns and turn them into creepy, kooky bad jokes, not worth thinking about, nothing to see here, move along. . .