TEMPORARILY UNLOCKED

Today’s thoughts are inspired by the fact that I’m in the process of finishing a book that will presumably be my final dive into the U.S. founding period, and it’s a strange fact to me that it’s been about twenty years since I took my first dive. As I fight my way out of that region of our nation’s history, I’m struck by changes in the commercial publishing landscape since 2003, the year I made my first book deal. Where and how founding-era history and U.S. history in general fit into current trade publishing arrangements confuses me at the moment.

Then again, as with all meetings between the intellectual and artistic on the one hand and the commercial on the other, none of it’s ever made any sense. To borrow from the Temptations, it’s just a ball of confusion.

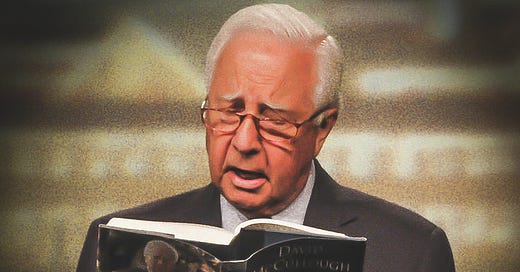

I don’t know how many subscribers to this blog are frequent readers of founding U.S. history commercially published for a general audience, so I’ll spend a moment on the fact that the founding period became a bit of a phenomenon at the dawn of the 2000’s. Known disparagingly by some, including me, as “founders chic,” bestselling biographies like David McCullough’s John Adams (2001) and Ron Chernow’s Alexander Hamilton (2004) came in the train of the book I see as starting it all, a kind of surprise bestseller, Joseph Ellis’s Founding Brothers (2000) , a group biography of major founding figures.

I don’t mean that McCullough, say, was following Ellis, since the Adams bio came out only a year after Ellis’s book, and McCullough was already a steadily bestselling pop historian; Ellis was a scholar crossing over to pop. Similarly, Chernow had already published commercially successful bios of finance titans. And the pop U.S. history market in general was strong. Doris Kearns Goodwin had published bestsellers on the Kennedys and the Roosevelts and was even then, in 2002, handily withstanding the fact that parts of her books were plagiarized. She would soon be moving right along.

In the 1990’s, too, Stephen Ambrose, a professor who had published a number of reasonably successful books, suddenly went into commercial overdrive, cranking out big, celebratory hit after big, celebratory hit on U.S. history topics. A mainstay of Simon & Schuster’s bottom line, Ambrose had something of a factory going, and he too ended up resorting to plagiarism.

At the end of the 1990’s, that is, pop U.S. history in general was a moneymaker.

Still, something new was in the air. The publishing industry suddenly got interested, to a degree it hadn’t in a while, in the founding period. As the historian David Waldstreicher once put it, the founders looked like an even Greater Generation than the WWII generation whose stories had reliably sold books. David McCullough was meanwhile getting on in years (though he’s still publishing [UPDATE: McCullough died on August 7]), and Ambrose had died, and those track records were aspirational. Publishers were hoping to launch new Ambroses. Some writers had reason to think of themselves as having such potential. And the founding period had new buzz.

Amid that particular ball of confusion, I got a book deal. There had even been an auction.

The confusion has only gone on since then. I may write more about this someday, but quickly for now: I was far from young, and at a kind of bottom-out point in my writing career. 9/11 had sparked my interest in the violence of the U.S. founding period, and I’d always thought the Whiskey Rebellion looked like a great story anyway. So with the rebellion fairly shakily in hand I got very luckily connected to a very powerful agent at the exact moment when the founding period looked hot.

Who was I, in book publishing? Nobody—and that was a good thing. When you have no track record, you and everybody else can feel free to imagine that your first book has a chance of breaking all records.

As a drug, I highly recommend that delusion. It was the headiest time in my work life to that point, and I went into what I can only call an altered state. Something happened. I don’t think anything like it will happen to me again.

In the spring of 2003, I went into the New York Public Library, stayed there every hour it was open for business, and when I came out, toward the end of the year, my life had changed in ways that made the founders-chic vibe—though without it, I never would have had a book deal at all—look incredibly lame to me. And ever since, kids, I’ve been publishing books that actively dissent from the genre in which they’re published.

That I do not recommend.

Let’s just say I was never going to be David McCullough. I am pleased, though, by the fact that my hate-tweeting McCullough’s Pioneers was enjoyed by a number of scholarly historians, and that my most recent book, Autumn of the Black Snake, spent three weeks on the indie-bookstore bestseller list. It’s been both a long strange trip and a short strange trip, with many exciting moments along the way, especially in the writing, and I have a strong appreciation for my readership.

In the meantime, even while I’ve been busy with writing these books and trying to keep things going, with the anonymous writing-for-hire that really makes most of my living, trade publishing of American history has changed. But how it’s changed isn’t clear to me.

I think key factors affecting current public interest in the founding period include the success of “Hamilton: an American Musical”; the Trump presidency; the proliferation of prestige TV; the impact of The New York Times’s 1619 Project; the further degradation of whatever nonfiction makes bestseller lists; new entry into the founder-bio space by women writers; and maybe a shift in the readership for the founding, beyond the white, male, heterosexual, and shall we say aging.

Sarah Vowell was always there, with a voice that’s always pleasingly offbeat. Right on the beat, though, in the sense of topic, is the bestselling You Never Forget Your First, by Alexis Coe. While the title does signal “cheeky” (that’s not me but the presskit), the book is a pretty straightforward bio of good old George Washington, a perennial character in the founder-bio genre. What’s different about Coe’s book is not only that it’s written by a woman but also that the author takes on, wittily, especially in the intro, male-authored Washington-bio traditions, and traditions of the broader genre itself.

And it’s funny cuz it’s true. Coe has invented the term “dad history.” I used to say “father-in-law book,” but “dad history” isn’t just more succinct; it clarifies the passage of the past twenty years or so (a lot of the fathers-in-law I was talking about are gone now). The potentially subversive thing, though, is that Coe is writing about the ultimate dad-book topic. There's nothing more old-school than “presidential historian,” and the culture at large may be looking for the next Michael Beschloss, though I hope not.

On another front, maybe an opposite front, and also announcing a subversive intention, the bestselling 1619 Project book offers what it calls a new origin story, reframing the country’s founding in terms of slavery and racism. As for the Hamilton musical, I know it’s not a book, but I think it’s had an impact on the “founders chic” conception, and it goes the other way, subverting casting conventions racially, in order to celebrate Hamilton and the founding, right in line with the Chernow bio it’s largely based on.

Maybe because I’ve always had to write against the genre that I’m writing in, I can’t see any of those examples of subversion as very subversive, beyond a very limited point. Indeed, there are ways in which their success signals a new brand of anti-radicalism. If people would rather read Coe than Chernow on Washington, that’s a good thing, to me, and goofing on dad history is a good thing too. But the other day, when I started thinking about all this, I was thinking that the whole publishing phenomenon of twenty years ago or so, derided as “founders chic,” has come to an end. And certainly it’s true that the authors who defined that moment have either slowed way down or become comparatively irrelevant.

But maybe founders chic goes on, in new forms that are actually chicer than the original. I owe my strange career in publishing books to the old phenomenon I’ve tried to combat. I may even have somehow outlasted it.

I wanted to burn that house down. But I didn’t. It’s just been superseded. Like everything else.

________________________

Further Reading

A Ken Owen essay on how some liberal scholars, generally anti-founders-chic, stopped worrying and learned to love the Hamilton musical. Follow links in the essay for further criticisms of the musical.

In 2004, David Greenberg discussed historians’ plagiarism scandals with reference to a book by Charles Peter Hoffer.

In 2017, I was invited by Boston Review to respond to Martha Nussbaum on the Hamilton musical. Her total brushoff remains a thing to behold.

David Head doubles down on Dad History (paywalled but you’ll get the idea).