Notes on the Fictional Nature of Nonfiction

with reference to “Get Back,” the Beatles, and writing nonfiction about the past

TEMPORARILY UNLOCKED

1. I was chatting with some people about what a jackass Michael Lindsay-Hogg comes off as, in the recent film “Get Back.” He certainly does, doesn’t he. I won’t review the goofball ideas Lindsay-Hogg had—and unabashedly brought up, right out loud—during the Beatles’ 1969 songwriting and recording sessions, which were also rehearsal sessions for a live concert extravaganza that never happened, and which Lindsay-Hogg was also continuously filming. I won’t review the annoying way he phrases his bizarre, at times even offensive suggestions. Or just the way he … stands there. (These are notes, so I’m not going over the “Get Back” basics, assuming you more or less know what it is, and might even have seen it, as so many have.)

2. The sheer embarrassment that is ML-H in “Get Back” seems to support the “Get Back” presskit conceit that the director Peter Jackson has now salvaged from degradation all of that footage, whose shooting ML-H oversaw, and has scrubbed away the pretentious git’s fingerprints, not only visually cleaning up the grim and grainy look-and-feel of the blown-up 16mm version used in ML-H’s eighty-minute cut—released in 1970 as “Let It Be”—and not only making the music sound very good, but also narratively correcting the grim and grainy story—the false story, it’s suggested, or at least the sadly un-nuanced story—told by that 1970 film, which did go out of its way to make it seem as if the lads were almost unrelievedly tense and unhappy during the sessions. The fact that PJ’s edit clocks in at more than six hours longer than ML-H’s edit further supports the current story that the new cut tells a fuller story, with the implication that the fuller story, and the current story, are the truer stories.

3. If you’re interested in the Beatles, there’s no question that the PJ version gives you a lot to chew on. Like, a lot. I’m quite interested in the Beatles, though I’m more interested in the music of the earlier Beatles than I am in the music of what I take to be a longish breakup period first audible on the White Album. Today's notes aren’t about the Beatles, though. I could go round and round all day about the propositions I just threw out there. Just not all day today.

4. A major thing that I got out of the “Get Back” edit is that the four young men and their various supporters and minders and helpers were indeed occupying a living hell while being filmed during those sessions, a hell which of course involved their difficult interrelationships, but which was also both more general and more immediate than that. I mean, a clock was ticking down, and nobody had any idea what the work product(s) were supposed to be, or what they were even really doing there or wanted to be doing. They had to keep dredging up new songs, writing, learning, teaching, and working on them, barely getting one song half-clear before trying another one, even while going around in endless circles over what it was all for, whether they could get it done on time, or get it done ever—with literally nobody in charge, all managerial support gone, and the whole mishegas getting filmed, all day, every day. It’s the Artist’s Nightmare. I was freaking out most of the time I was watching. A horrible situation, essentially imposed on the Beatles by the Beatles: that’s what’s been documented. Or depicted.

5. The way I remember ML-H’s “Let It Be” edit, ML-H is not a character, the way he is in PJ’s version. I suspect that ML-H was shrewd enough, as a director, to leave out the role he played in creating the chaos of the painful situation I just described. PJ is shrewd enough to make sure we see ML-H’s role clearly and memorably. There’s no way to come away from the later director’s edit with much personal regard for the earlier director. From what I’ve heard from critics and people talking, the general takeaway is that ML-H is deserving of derision at best. Because ML-H did an uninhibited job of making kind of an ass of himself, more than fifty years later PJ had an easy task.

6. The whole idea that it was OK to just turn on cameras and let them roll for days and days and days was totally novel at the time, and in a way really screwed-up. Documenting the creative process (of all things)!

7. Frederick Wiseman’s work comes to mind—but the shooting process for his 1967 breakout, “Titicut Follies,” was supposed to be intensely hampered, contractually, by the staff of the institution he was exposing; in the end, the state of Massachusetts got that film banned for shooting too much. In ordinary life today, cameras are almost never off. People watch reality TV, post videos of themselves on vacation, do TikTok memes, spy at home on kids, pets, and servants and demand that delivery people dance. But nobody ever heard of any of that stuff back in ‘69. I know this will sound impossible to you kids, but many ordinary people actually had no idea what they looked like on film. The camcorder was yet to be. Home movies were brief and (usually) frenetically shot in short clips. The first reality show I ever saw, PBS’s “An American Family,” was aired four years after ML-H’s shoot of the Beatles. Watching either “Get Back” or “Let It Be,” what we get back to may be the first step in a process that has taken over our lives.

8. In context, it seems a starkly strange fact that the freaking Beatles submitted themselves to something nobody had ever submitted themselves to before, almost a kind of mad-scientist experiment on human subjects—those being filmed, of course, but also us, whose limits on voyeurism had not then been fully gauged. The whole project could be seen as quite creepy, if our voyeurism hadn’t turned out, since then, to have no limits. (You couldn’t have gotten away with releasing eight goddamned hours of this stuff in ‘69!)

9. Even trying to keep all that in mind, the footage we’ve been watching can’t help but seem far more normal to us than it was when shot. ML-H’s edit, providing only an eighty-minute glimpse of a weeks-long experiment, mutes the weirdness. PJ’s edit has been played up publicly as making the vibe less weird than “Let It Be,” more fun and lighthearted, but wittingly or not, the sheer relentless length of “Get Back” exposes the spy-cam-at-the-freakshow aspect, the proto-“Big Brother” format, and thus exposes that it was really the Beatles and ML-H who collaborated in pioneering it. Thanks so much, boys.

10. Back to Wiseman for a moment. As I remember the 1970 “Let It Be,” despite its relative brevity it recalled Wiseman more than “Get Back” does, despite the latter’s great length. In my memory, “Let It Be” was intended to feel radically, grittily verite: sometimes it wasn’t perfectly clear what was going on or what we were supposed to think the themes and issues were. “Get Back” does a lot of broad, obvious signposting, nudging us to identify what’s significant, what’s really going on, etc. That’s an effect of the sometimes aggressive editing style, of course, but it’s also added, with peripheries: the long montage intro telling us who the Beatles actually were; the day-to-day-calendar countdown; and some onscreen text. At the end of the first part, that approach goes all the way and adopts a mode familiar from real-estate reality TV: Coming up, Glyn Johns and Michael have a concert suggestion for Paul that will finally make him happy! That setup occurs over a shot of Johns and ML-H whispering to McCartney and McCartney starting to smile. It’s a shot that anyone who watches real-estate reality-TV will know, without having to think about it, may well have nothing to do with the real-life moment when it was first suggested that the band record a live concert up on the building’s roof. Or it may.

11. “Get Back” also made me recall that when I was in the bullseye of the target audience for Beatles-album releases, the release order wasn’t really “Sergeant Pepper’s,” the White Album, “Abbey Road,” and “Let It Be,” but “Sergeant Pepper’s,” “Magical Mystery Tour,” the White Album, “Yellow Submarine,” “Abbey Road,” and “Let It Be.” Going back even to its two earliest movies, the band had always been into narrative media projects that people don’t talk about so much today: MMT was a British TV special, YS an animated feature. One side of the YS LP didn’t even have Beatles recordings. It featured orchestral tracks from the movie’s score. Weirdly enough, the U.S. release of “Help,” the only one I knew upon release, had a bunch of boring movie music on it too. (Why?! We used to lift the needle and skip those tracks!) The big trick nobody had yet figured out was how to marry rock and TV, and such, I’ve learned from “Get Back,” was one of ML-H’s obsessions.

12. Another thought while watching: At least nobody was shooting film when Dylan and the Band were recording at Big Pink.

13. When everything is documented, as everything is now, does the effect become roughly the same as if nothing were documented?

14. These aren’t documents, of course, in the sense of records of fact. They’re stories, —everybody already knows that—operating via a series of effects. What technical magic did PJ have to do to get the thing to look and sound so good? The high quality of “Get Back,” compared to “Let It Be,” doesn’t reflect some greater fidelity to how things looked or sounded in real life. Nothing looks or sounds in real life the way it looks or sounds in a movie. A movie, everybody already knows, is an image of how things look and sound in real life, and generally the more impressive the realism, the more sophisticated the technology, the artifice. Weren’t the Beatles among the first in pop—I said among—to abandon the idea of an audio recording as supposedly a mere record of a live performance (it never was anyway) and openly start using “recording” technology not to record musical events but to create them afresh?

15. The way I remember real-life 1969, by the way, it looked and sounded a lot more like “Let It Be” than “Get Back.” But memory is even more fictional than nonfiction. I doubt I recall “Let It Be” very accurately. Or, for that matter, “Get Back.”

16. I’ve had some very limited involvement with video production, far greater experience with nonfiction narrative prose. I’m talking, that is, not as a critic but as a practitioner when I say that the whole goal of turning something captured “on the record” into a narrative is to create an impression of perceived truth, at best, or to create a falsehood, at worst, and the lines between the best and the worst aren’t always bright, putting it mildly. It can take eight hours for the resulting impression to unwind, or eighty minutes, or whatever: it’s still nothing but an impression, nothing more nor less than what the artist hopes to say or to do about the subject. The impression also exposes a lot, along the way, about the artist. Another Artist’s Nightmare.

17. Film never caught John Lennon, for example, doing some of the things he did in real life that might make us really hate his guts if we saw them on film: in the movies, he’s forever our John. Only what’s shot, edited, and released is relevant to the story. It’s a happy fact that I myself, at 29, never ran my mouth in an embarrassing manner like ML-H. You can be sure that this is true because I’m lucky enough to have lived most of my life in the time of no footage.

18. Many people love the rooftop concert. It’s a brute fact that it was indeed the insufferable ML-H who, with Glyn Johns, had the idea, and ML-H who, at least as crucially, set up the many camera positions, including the longshots from another rooftop, that gave us the rooftop concert. Otherwise the rooftop concert wouldn’t exist—neither the event that evidently took place one day in London in 1969 nor what we really think of as the rooftop concert, which is the film footage of it. Decking had to go down on the roof so it wouldn’t collapse from the weight of all the equipment. All that stuff had to get humped up there, set up, connected, tested, etc., etc. To me, it remains a phenomenal moment, and 100 bad ideas to get to one good one is a pretty decent ratio, at least where I come from. Keeping in mind what we’ve never had to witness John Lennon do on film: hate the sin, not the sinner; love the art, not the artist. If you loved “Get Back,” maybe spare a thought for the effete young wackadoodle who gave it to us, and who presented his own version, in 1970—his own impression of the Beatles—and who presented it on a scale that we might call, ironically enough, somewhat more … modest? … than the new edit.

19. Now this has gotten too long for me to make the connections with writing prose nonfiction about the past that I set out to make. But the connections are there.

20. Oh, are they ever.

___________________

Sorry, no further-reading links this time—can’t think what I’d link to! So here’s a postscript. I read somewhere that about two weeks after the close of the exhausting sessions we’ve just been made privy to eight hours of, the Beatles started sessions for what would become “Abbey Road.” George Martin said he wouldn’t produce it unless the lads—especially John—explicitly agreed to return to the scheduled, normal, old-school mode of recording albums they’d used so many times before. It didn’t go exactly that way, but still: whatever you think of “Abbey Road,” there’s just no way anyone thinks “Let It Be” is the superior or more important album, hellish chaos not being the key to creativity, it turns out.

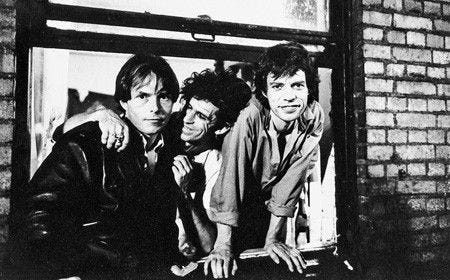

Oh, wait, here’s something, a Michael Lindsay-Hogg rock-TV experiment:

(Eric Clapton guitar, Keith Richards bass, Mitch Mitchell drums.)