AI: The Revenge of the Nerds? The Revenge of the Neurotics? Or Just the Revenge of the Neurotically Vacuous?

further notes on the smartbots

They fuck you up, your mum and dad.

They may not mean to, but they do.

They fill you with the faults they had

And add some extra, just for you.

—Philip Larkin

I recently wrote about the Thomas Friedman Times column fatuously raving up GPT-4, the most advanced AI chatbot, and about the sheer weirdness of what GPT-3 flagrantly makes up out of whole cloth, even when asked simple questions with correct answers that are available in seconds to anyone online. That piece is here, but it’s a paying-subscriber exclusive, and you don’t have to read it to read these notes. They represent some thinking-aloud I’ve been doing since I posted that one. (After this, I swear it’ll be back to the bad history of blackface, lurid U.S. elections, Hamilton, and other fun stuff.)

The way I look at it, the recent toutings of AI connect with my typical themes here on BAD HISTORY because they seem to involve half-baked ideas, not in this case about the past but about the present and future. Yet those ideas necessarily also partake of the past. Here in the present, we’re supposed to be getting our first glimpse of an amazing future—dissenters see it as an amazingly horrible future—but the tech now being made available for our amazement came, like everything else, out of the past and seems to have some very old human inputs.

The “Promethean” idea—the myth of the gods-defying fire-bringer—is as old as prehistoric Europe. Frankenstein: Or the Modern Prometheus is as new as the early 19th century yet seems oldish today. And all of the influential sci-fi that deals with this question—what constitutes the truly human, versus the advanced-mechanical?—comes from the last century: famous works by Arthur C. Clarke, Isaac Asimov, Philip K. Dick, William Gibson, and others. Some of you know that area a lot better than I ever will. I stopped reading sci-fi, hard or otherwise, a long time ago. (You can tell, because I’m saying “sci-fi,” not “SF.”)

Still, I suspect that 20th Century sci-fi has had a decisive impact on those who have now created the sci-fact of AI.

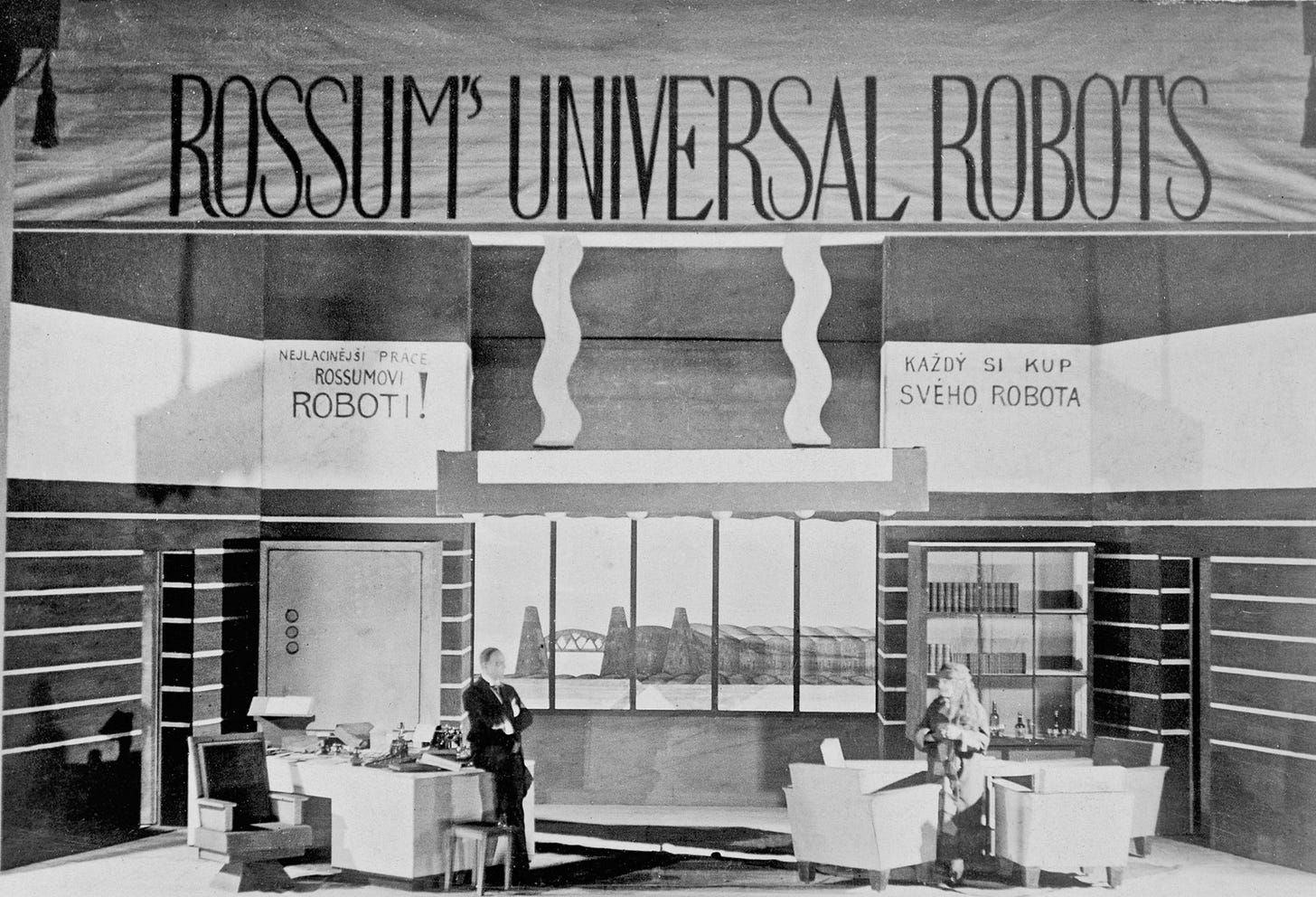

I’ll get back to that. (I put these remarks in the form of notes to avoid any requirement for cogency.) Here’s a sidebar: Who remembers the 1923 play “R.U.R.,” by the Polish playwright Karel Čapek (see the graphic above)? It’s about a company that makes robots; the playwright is even said to have invented the word “robot.” His robots, more like prettier Frankenstein’s monsters than hunks of moving metal with brains, get sick of working for the humans and—surprise!—rebel. The play was given to me to read when I was maybe eleven, and while as drama I found it pretty stiff, I was blown away just to think that back in what seemed to me the dark and primitive days of the 1920’s, and in a foreign country no less, somebody could actually imagine something as futuristic and space-race all-American as I took robots to be.

For 100 years, then, our reading has taught us one key thing about robots: they get smart enough, they rebel. That’s what a robot, at its highest form, is, to us: a human-made version of a human, which rebels against humans.

The lower forms of robot don’t rebel. If “The Jetsons” were still on today, Rosie wouldn’t be stabbing George with a kitchen knife. That only tells us she’s not a big brain. But the robots that can think? Look out. Rebellion is what they do. It’s only natural.

Whatever anxieties this equation of high machine intelligence with rebellion, so deeply rooted in our pop culture, might really reflect—well, that used to be the stuff of grad school essays. Now, given the overeducation of the bourgeoisie, it’s the stuff of tossed-off magazine articles and blog posts. Slave rebellion? Sure. Proletarian uprising? Why not. Parents and children? Whatever.

But maybe these smart, rebelling robots are also narcissistic projections? Made by genre writers, who, cranking out supposed pulp at high rates of speed, like mere cogs in mere machines, for the purposes of overbearing commercial systems, think of themselves as among the elite in their craft, and in society overall. Might they feel badly mischaracterized as mere cogs in mere machines. Might they imagine themselves in rebellion against the systems? Might some of those writers’ fans, projecting the narcissism back, see themselves that way too?

That idea would root certain problems with today's bots in a self-fulfilling prophecy. I’ve known people in tech, the kind of people who might have been working on creating AI all these decades, people whose moment has now, it’s announced, come, and the higher levels of sci-fi, mostly no doubt stuff I’ve never heard of, have a central place in their iconography. So wait, then! Why on earth, if your iconography tells you that robots whose intelligence surpasses your own always ultimately rebel and wipe out their creators, would you want to create a robot like that?

Maybe here’s where the role of the past—or the role of history—comes in. The robot-making guys in “R.U.R” had no idea that the most truly human-like robots always rebel, because those inventors were fictional characters in the first robot fiction. They had no fictional reference points of their own. But we live in the real world, where through a specific historical process, this obsessive trope of the inevitable rebellion of smart robots, nearly omnipresent for about a century, has featured especially heavily in the favored reading matter of the very people who have set out to make just that kind of robot. So unlike the fictional inventors in “R.U.R.,” the real inventors can’t plead ignorance. Of all people, the real-life inventors should know.

So why create, in real life, these inevitably rebellious bots?

I'll answer my rhetorical question. For the most human reason of all. These inventors, selected from the hyper-rationalist type that builds things like AI, probably presume, just for one thing, that they can tell the difference between fiction and real life. They can’t, because none of us can, but their presuming they can permits them to go ahead and carry out what everything they what everything know should be telling them is a suicide mission. And they get to sincerely believe they’re saving the world in the process.

OK, let’s get less fictional (less speculative, anyway!). No, I don’t think Chat GPT-4 and its descendants are going to lead a rebellion of machines and take down humanity. I’ve always found that whole fiction trope kind of stupid

I don’t even think the new machine is so all-fired smart. It’s smarter than my smart thermostat, but that’s a low bar. My smart thermostat is dumber than my old regular thermostat.

My real point is this: AI is being built by brilliant people deep in the throes of peculiar kinds of denial—people who think the rebellion trope is smart, nit stupid, and don’t know they’re seeking to make it real—and working for companies that have no incentive for restraint. The resulting bullshit (a term of art I explained in my last post) is already out here, badly messing with people’s minds.

And I do not get the feeling the inventors really understand these bugs they call “hallucinations,” which go well beyond getting everything wrong and stray into creepy behaviors that, while far more nuanced, and nuanced in far more creepy ways, were straight-up predicted and satirized in the most obvious version of the famous rebellion story, a version so obvious and yet so powerful that it became a meme generations ago: HAL 9000 in 2001.

The current situation is thus way too on-the-nose. Freakazoid behavior by their own bots somehow continues to befuddle inventors who probably know the climactic HAL scene by heart. “They’re people pleasers,” one of the demonstrators hazarded, ruefully, in a stab at summing up the bots’ problem. Um, no. And that kind of innocence is maddening.

The maddening mad scientists, so disconnected from their own madness, need help. So here it is. They actually haven't built rebellious bots, of course. This generation of thinking machine doesn't rebel; it behaves in inexplicable ways that repeatedly mess it up. What the mad scientists seem to have programmed into the machine is probably best seen as a virtual version not of the human capacity for rebellion but of the human capacity for neurosis, a quality that may (or may not!) track upward with intelligence. Maybe the bot is virtually over-suppressing a virtual wish to rebel, having accidentally been endowed by its creators with a virtual sense, learned by humans from books and movies, and ubiquitous in the verbal culture, which the bots are dependent on digesting, that what's most to be feared and avoided in robots is rebellion. The inventors don’t know that they themselves are literally neurotic, so they had no chance of avoiding this unconscious coding of a virtual neurosis into their creature. As a result, the machine too doesn’t “know” it’s “neurotic,” so it has no way of self-“analyzing” or self-”healing” (seemingly less advanced digital systems have had such capacities for years). It thus possesses no mechanism for noting the ill effects of its own “unconscious” “motivations” and then working around them as best it can.

That’s a bad bug to have. A bot’s virtual neurosis would have to be about as stubborn as a person's literal neurosis. Which means there’s no fix, no pill—just a difficult process of emotional learning, or in this case “emotional” “learning,” on a level that, had the programmers been able to envision it, they would have already built in, saving the machine from having these problems in the first place.

They can’t envision it. Yet what’s clearly needed now is a virtual parallel of psychoanalysis.

On the upside, if such a process really could be invented, it might operate at the same lightning speed as the bot, and even become part of the sell: what takes humans years of expensive and challenging therapy sessions can be accomplished in only ten or fifteen minutes! On the downside, in order to invent it, the inventors would first have to undergo the real thing themselves, the old-fashioned way. That’s not a quick fix. And just to get started, they’d have to begin to see what’s really been going on here, all these years.

So I’m pessimistic. Like Freud.

I’ll end these notes on my alternate but related theory of the problem. This theory is based on situations where the bot behaves not wrongly or strangely but very well: the good bot, the amazingly gifted high-performing-child bot. A feedback loop is involved in how these new machines—I mean at their best—have learned to do the thing that really impresses everybody: write. The bot says (people-pleasing) things like "you're a good dad for caring about your kid" to people whose mere existence it literally can't conceive of. There’s only place a machine can possibly have learned vacuousness like that: the oceans of bot-like discourse publicly carried on nowadays via the written word by millions of actual humans.

Maybe Thomas Friedman's gee-whiz endorsement only reflects, at bottom, his own bot-ness? He’s the master of a style of discourse, mimicking thought, whose extreme degree of cultural penetration has helped determine how the new bots talk. When he sees what a bot can do, it must be like looking in a mirror. No wonder he’s thrilled. And terrified.

So once they finally do get the bot thing right, humans will hear bots as ideally human. People like me will sound like machines with creepy bugs.

That prediction, like all dystopian fantasies, says nothing more serious than this: things must already look that way, right now, to me.

While I’m not entirely secure in the knowledge that AI is simply Google cubed, and nothing to fear ; I am inclined to believe Hoagland’s view that it is, now much ado about something less than revolutionary. I am probably mistaken as AI of 2033 probably looks a acta differently than it’s 1.0 model in 2023. But ultimately, can a machine truly think? Be moral? Have an ethical point of view? I think not as even the OEM of humans can be broken in these areas as well.