(This is the second entry in a three-part series. Part One here. Part Three here.)

In my last public post, I looked at the Soviet-influenced politics and music of the Almanac Singers: young leftist musicians of the late 1930’s and very early 1940’s, the group that gave Pete Seeger his start as a performer and at times included Woody Guthrie. I discussed how their “peace songs,” protesting any U.S. involvement in WWII, were really pro Hitler-Stalin-pact songs, and in that sense, not to put too fine a point upon it, effectively pro-Stalin songs, and in that sense effectively, if only for a moment, pro-Hitler songs, though that’s the last thing the Almanacs ever intended their songs to be.

The path by which Seeger, Guthrie, and the Soviet-influenced U.S. left as a whole came to perform a perfect one-eighty and wholeheartedly support U.S. entry into the war, even before the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor, is part of the story I’m telling. But I also said in Part One that the Almanacs’ music, to me, is bad—both as music and as politics—in ways that have resonated through a long phase of American popular culture still ongoing. So that’s what I’m going to focus on first.

The phase of the culture I’m talking about is no longer by any means “postwar,” of course. It’s about eighty years old now, with a multitude of complexities and nuances. But I think some of its elements and imperatives were formed in WWII and the war’s aftermath and continue to affect ideas about the relationship of political protest to music, among other things.

So just below there’s a song by the Almanac Singers, recorded way back in 1940, for 78 rpm, and previewed in Part One, that raises a lot of questions for me. In September of 1940, Congress passed and FDR signed into law a military draft bill, the country’s first-ever peacetime draft. The Almanacs, following the party line, objected (sorry about ads on these videos):

It’s all a matter of taste, of course, but that singing is pretty unbearable to me, and Seeger’s vocal approach had a powerful influence on vocal styles in the genre that would come to be called folk, sometimes urban folk, an ongoing mode of revivalism, filled with ideas about “the folk” and what the folk’s politics should be. It’s not that Seeger’s singing here is somehow inauthentic. It’s that he’s straining every nerve to seem—even to be—authentic, and that wrongheaded effort’s overall musical effect makes me cringe.

So what: a New England WASP thinks he sounds like a poor Southern man who may somehow be both white and black? Hey, everybody in pop is also in theater.

Yet with every note, Seeger’s way of singing pounds us with news that this isn’t theater, and isn’t pop, it’s the real thing—also that he's quite sure he’s already got us believing him. That sound makes me feel badly presumed upon, pushed and shoved and crowded by a line of bunk. It’s less the words themselves—nothing to write home about either—than how the words are sung.

I know—not everybody will hear it my way, putting it mildly—but I bring up these aesthetic judgments and combine them with political judgments because that’s exactly what the Almanacs did. To them, capitalism was capable of producing only a cheap, superficial, soullessly commercial popular music: bad. They thought they were tapping into the good: a deeply expressive “people’s music,” the music of the folk, the authentic upswelling of an anticapitalist American spirit emphasizing community and cooperation.

The main vocal tactic for delivering that message, it seems to me, was to expend a lot of energy on being quite pleased about embodying the good. But I know some people still like that sound.

One problem for the Almanacs’ ideas about tradition in music is that traditional music is nothing like what they wanted it to be. It doesn't sound like them, for one thing, but also, regarding repertoire, any truly authorless songs, originating so far back that they might sound like spontaneous upwellings of the whole people, are about things like fighting and murder and drinking and pregnant women abandoned and existential isolation and the doings of lords and ladies.

And when it comes to the American work songs that the folkies liked—because they’re about, you know, work—those songs originated more often on the blackface minstrel stage than in the lives of real people. “I’ve Been Working on the Railroad” is just one of many songs originally sung on stage by white men in blackface making free use of the “n” word.

Which gets at the bigger problem. There isn’t much traditional music around here anyway. The roots of almost all American vernacular music are to be found in the forms produced within the capitalist commercial arrangements the Almanacs despised. These youngsters showing up from New York at strikes and rallies were trying to reach the people, via the people’s music, giving them the old stuff, “straight,” as they liked to say, instead of the opium-of-the-people slop they thought the people were being fed by the radio to distract them from class struggle. But if the folk have to be educated in what folk music is, how folk is the music?

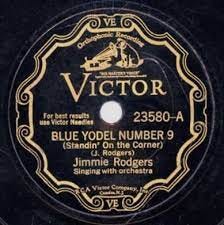

And what the Almanacs were trying to give the folk wasn’t folk anyway, if folk means what the Almanacs imagined it meant: music original to the people, handed down through generations, untainted by crass commercialism. “C for Conscription,” embedded above, is a classic example. It’s really the 1927 Jimmie Rodgers song “T for Texas” with new agit-prop anti-draft lyrics. If the recording sounds like Seeger’s tapping into an old form with both black and white elements, that’s partly true. By the time both Jimmie Rodgers and the recording industry came along, black and white musicians had been influencing each other for years. Rodgers, a white man, wrote and sang what he called blue yodels, blues-form songs—heavily influenced, that is, by forms especially associated with black artists—yet including yodeled turnarounds. (Maybe because the yodeling is wordless, to me it’s the strongest part of Seeger’s recording.)

Rodgers sometimes performed in blackface—of course. And on some of his recordings, Louis Armstrong played trumpet and Lil Hardin Armstrong (one of the first women to lead a jazz band) played piano. Here’s an example:

I’ve looked elsewhere at how commercially influenced all of the 19th-century, pre-recording, supposedly folk traditions were—black, white, borrowed, stolen, masked, and shared (I’ll have other examples in another post, including Hank Williams’s “Lovesick Blues” and The Carter Family’s “Wildwood Flower.”) For now, I just want to note that there’s no music more commercial than the music on which “C for Conscription” is based. Jimmie Rodgers’s recordings more or less launched the country-music industry, via the genre then called “hillbilly.” That made businesspeople and investors in radio, theater, and recording a lot of excess capital.

So in 1940, with “C for Conscription,” the Almanacs were proposing to offer working people who by then would have been listening to Ernest Tubb or Frank Sinatra a sound supposedly originating with the people themselves long ago and handed down traditionally, with the addition of some antiwar lyrics approved by the Communist Party for the avowed purpose of aiding the liberation of those very people. Yet the sound was really just a slightly outdated version of the capitalist Nashville-industry music of Tubb and others, almost all of which is just far better than anything the Almanacs had to offer.

And such was the snobbism of the folk revivalists regarding the pop charts that they ranked their own thuddingly obvious propaganda lyrics higher than the lyrics in songs produced by the capitalist New York City industry, written by, say, Yip Harburg, Dorothy Fields, George Gershwin, Irving Berlin, and Duke Ellington, and sung by Sinatra, Ella Fitzgerald, and many other fine artists.

These delusions of the Almanac Singers as to the nature of their own music—political delusions of communistic purity, historical delusions of the development of the American vernacular, aesthetic delusions of what constitutes quality in music—were totally unaffected by an astonishing reversal they had to make, one day in June of 1941. Seeger was playing a rent party when somebody rushed in with the news that Germany had invaded Russia. The Hitler-Stalin pact was broken.

As we near the end of this story, I’m again struck by the mix of horror in Europe and goofiness in the U.S. with which I began Part One. Because now we’re back to the Holocaust.

And we’re in Ukraine, where horror reigns as I write this, and from which horrible questions about U.S. policy are now pressing. Neither the Almanacs nor anyone else in the U.S. knew it in 1941, but as bad as things had been before, the German invasion of Ukraine wasn’t only a breaking of the pact and a pitting of Stalin against Hitler, to the great hope of the western democracies. It also took the policy of exterminating Jews to the levels represented—but only represented—by the most famous mass killing, at Babi Yar. So the juxtaposition is nearly incommensurable. Another reversal of the party line ensued, and Seeger and Guthrie had a rushed conversation about the need to turn on a dime. In Seeger’s memory it went like this:

“Why, Churchill said ‘All support to the gallant Soviet allied!’”

“Is this the same guy who said twenty years ago, ‘We must strangle the Bolshevik infant in its cradle?’”

“Yep. Churchill’s changed. We got to!”

And so, as instructed by The Daily Worker, the Almanac Singers now urged U.S. entry into the war with all the fervency they’d brought, literally days before, to opposing it.

Regarding their approach to music, they changed nothing. With the “peace” songs canceled, they’d lost a good chunk of their repertoire, so they started cranking out identical songs in favor of war. These songs weren’t recorded until right after Pearl Harbor, and that put the young rads right in the new, gung-ho, war-effort mainstream.

I’ll close with two of those songs.

First, a rewrite of “Old Joe Clark,” a standard Appalachian hoedown. I don’t know how the Almanacs could have thought that this ditty wasn’t at least as bad as any of the war-themed pop songs that started airing on the radio after Pearl Harbor—a few of which actually hold up beautifully today.

And finally “Dear Mr. President,” embedded below. This is a “talking blues”—Guthrie did some good ones, and so would Dylan, under Guthrie’s influence—but I find this one downright offensive for its patronizing effort to inhabit and speak for the ordinary American guy of the day and brutally define that guy’s views per the new party line of 1941. Some of the Almanacs’ labor songs are infected with that spirit too, and it was catching. I don’t mean the talking blues, though that too was catching, and I don't mean necessarily the Communist Party line, which would slowly be abandoned—it’s the patronizing earnestness, working lockstep with ideology, which can take a number of song forms. Christopher Guest demolishes the whole ethos—both vocally and compositionally—in the film “A Mighty Wind,” especially with the song “Skeletons of Quinto,” so spot on that it goes beyond parody and becomes hilariously painful. (The talking blues form, by the way, was invented in 1926 by a commercial country artist named Chris Bouchillon.) Here’s “Dear Mr. President”:

But not all “protest” songs are bad history adding up to bad music. So I think there might have to be a Part Three on this subject at some point.

EXTRA: Two more recordings just came to mind: the Smothers Brothers’ “Mediocre Fred” and Dylan’s “I Shall Be Free No. 10.” Both are from the 1960’s; they parody the talking-blues mode in the urban folk revival. The Dylan song has verses where I sniff totally fed-up disdain for that young artist’s mentors in the American genre then called protest music, which had originated with the Almanac Singers. And the Smothers’ number is just classic them.