Ten Years On

The founders’ disingenuous politics around the right to bear arms is (still) killing us.

I’m unhappy to be re-posting this piece on the Second Amendment from ten years ago, because it was ten damn years ago, and because things have only gotten worse since then. It ran on AlterNet, in August of 2012, following some mass shootings in Colorado and Texas—that’s about four months before Sandy Hook—and because it was written for that audience, it has a bit of a different style from the things I usually post on BAD HISTORY, but it’s pretty much all I can do by way of responding here to the latest horrible incidents, so I won’t mess around with it now, though I will put a few notes at the bottom. . . .

______________

August 18, 2012

Amid horrifying reports of American gun violence — the latest from College Station, Texas, yesterday, and Aurora, Colorado, last month — it’s natural for Americans on all sides of the dire issue of gun control and gun ownership to invoke our founders’ legacy regarding arms and rights. The Second Amendment to the U.S. Constitution famously asserts a “right of the people to keep and bear arms,” and liberties secured in the first ten amendments have a special place in the hearts of Americans.

Paul Ryan, for example, the presumptive Republican nominee for vice-president, champions rights of gun owners. Of rights in general he believes that the U.S. is unique for having been founded on the idea that they “come from nature and God, not government.” Ryan’s attitude reflects a pervasive desire, across the American political spectrum, to ground current political positions in what many Americans see as absolute rights, protected for us by our founders in the Constitution. Determining what the founders meant by a right to bear arms has long seemed critical to winning arguments for or against gun legislation. After every horrific mass shooting, debate breaks out over what the amendment, in the most basic sense, means. Both sides are sure they know.

The debate is futile. Any serious effort to address whatever lies behind the astonishing rate of American gun violence should begin not by appealing to the founders, but by criticizing the legacy they bequeathed us on liberty and arms. The Second Amendment came to life in a climate of cognitive dissonance and lack of public candor. The resulting confusion has enabled us to indulge in a deadly mix of immature fantasy and apodictic certainty, disconnecting us from reality to a degree that we can no longer, putting it mildly, afford. A more grownup and realistic confrontation with the process that gave us our constitutional rights — bitter medicine, perhaps — might be a precondition to diagnosing, at least, what seems to ail us so desperately.

History?

The realpolitik in which the Second Amendment was framed, during the first U.S. Congress of 1789, has some unedifying features. They’re illuminating. The amendment was a response to the federal government’s control of state and local militias, and the federal power to raise armies and create a navy, as set out in Article I, Section 8, of the Constitution. That provision had been among the most hard-fought at the Constitutional Convention of 1787. Delegates committed to state sovereignty feared — rightly enough — that if the federal government were empowered to control the state militias, states would lose sovereignty. In that elemental debate lies the beginning of a perennial American disingenuousness regarding arms — and regarding rights.

Delegates led by James Madison wanted to create a national government, directly obligating and obligated to all citizens throughout all the states. To achieve it, they had to play down how entirely they wanted it: if they admitted how nearly utter the states’ loss of power would be, in their emerging vision, they’d never get a national government. His own convention notes show Madison, along with other nationalists, minimizing the impact of the federal militia power, in particular, in hopes of soothing certain delegates’ fears of losing state sovereignty.

As we know, in the end the nationalists got more or less what they wanted. Despite concessions to their opponents’ ideas about state sovereignty, we became a nation. And in one area, the nationalists got exactly what they wanted: a constitutional provision giving the federal government control of states’ military institutions.

So when pressured to amend the Constitution, Madison continued to prevaricate. Former antifederalists in Congress and the state legislatures, resenting the federal power to control militias, were hoping to use the amendment process to regain some military control and thus retain some sovereignty. In the Second Amendment, Madison tried to defeat those hopes by placating them without really addressing them. The amendment gestures vaguely at state sovereignty in a way intended to make little practical sense.

Permanent Doubt

We argue fiercely today about the intended relationship between the famous opening phrase (“A well regulated militia, being necessary to the security of a free state,”) and the famous main clause (“the right of the people to keep and bear arms, shall not be infringed”). But it’s fruitless to try to nail down that relationship, to hope to prove for good and all that the opening phrase is or is not a preamble, or that a preamble does or does not determine the meaning of a main text, or that a “being” phrase means something different from or identical to a “whereas” clause.

The sentence is weak. The weakness is deliberate. Madison couldn’t afford, on the one hand, to let the amendment seem to contradict the hard-won federal military power in the Constitution’s main body. He couldn’t afford, on the other hand, to underscore too strongly for the states’ comfort the overwhelming nature of that federal power. He seems therefore to have resorted to a preamble-ish-like phrase (no other amendment in the first ten has a preamble), referring to the supposed benefits of state militias, while employing a loose “being” construction — technically the “absolute” phrase, largely avoided by modern English, for good reason — that leaves the phrase’s grammatical relation to the main clause permanently imprecise, and thus causes, despite so many assertions of certainty, permanent doubt.

Another dissonance, woven into the text itself: the opening phrase refers to a “free state”; the main clause refers to a “right of the people.” In 1789 Madison was still trying to move sovereignty away from the states and locate it in what the Constitution’s preamble calls “We, the people” — citizens of the whole United States. Some today who favor assertive gun laws follow the historian Garry Wills’s famous argument that the opening phrase refers to a state power, not an individual right, and that whereas in the Fourth Amendment, “the right of the people” does refer to individuals, in the Second it doesn’t. Meanwhile, defenders of a right to private gun ownership insist that when the founders said “a well-regulated militia,” “a free state,” and “the right of the people,” they simply meant that private individuals must remain armed against potential tyranny.

However well or poorly such arguments are formed — Wills’s, while tricky, is exhaustively well-founded and logical; many of the gun advocates’ are not [UPDATE: Also see Justice Scalia’s grammatically and historically uninformed opinion in District of Columbia vs. Heller, 2008, where the Supreme Court decided for the first time that the right is an individual one] — both sides in the current gun-rights debate are trying to make sense of something intended by its author not to make that kind of sense. Madison wasn’t trying to protect or rule out a right to individual gun ownership. He was trying to conjure a mood of grudging, semi-coherent consensus, to establish nationhood. To that end, he denied real divisions and real effects and wrote that denial into founding law. Seeming to contradict even while declining to contradict the federal military power in the Constitution’s main body, the Second Amendment, as written, passed, and ratified, is legal gibberish.

Instead of forever appealing to the founders’ wisdom, we must learn to manage, somehow, the unintended consequences of their slippery politics. To that end, we must face up to them. Without the nationalists’ slipperiness our nation might not have come into being. It did, and here we are. Neither Madison nor any other founder could have envisioned the modern uses that the Second Amendment has been put to (or that arms have). For political reasons having little to do with our struggles today, the founders built a murky relationship between guns and liberty into American culture, stunting, all these years later, much-needed public discussion of what has long since become a deadly national problem. To begin to free ourselves from incoherence, to begin thinking publicly about how we might drastically reduce our penchant for gun violence, we must face the stark fact that in this case, our founders don’t have any help to offer us. We’re on our own.

___________________

Notes (May 31, 2022)

1. The piece is deliberately a bit crude in its approach to Madison, but I find I can more or less stand by it, for these purposes.

2. Ten years on, after every big, horrible gun-violence event, I see a lot of gun-control people out here trying to explain to the public that the amendment really doesn’t mean what the gun people say it means, etc., etc., as if by finally clarifying the text, we can finally all agree on some gun control. I don’t see any hope in that approach. I think we’re stuck with the amendment, stuck with the Heller decision regarding its meaning and, at the moment anyway, stuck with a rightist Supreme Court. Changes in policy may be made, but not from getting all essentialist about the original meaning of the amendment’s text, a circular, even academic discussion that might almost be intended to defeat realistic progress on gun control in the modern world we really live in.

3. The big second-amendment explainer prevailing lately, in keeping with current trends in what’s known as the discourse, is to tell us that the amendment was passed—again, essentially—for the purpose of assuring the white South that it could keep putting down slave rebellions. The history of slave patrols is a study in itself—and of course they existed in the North too—but as you can probably tell from my ten-year-old piece, to me that line of thought represents yet another distraction. Yes, the Federalists were trying to placate people like Patrick Henry, slaveholder of Virginia, who opposed, among other powers granted the federal government by the Constitution, the power over the states’ militias. Henry did what he could to stir up southern resistance to the Constitution by raising anxiety, on a number of bases, about the future of slavery under the new system.

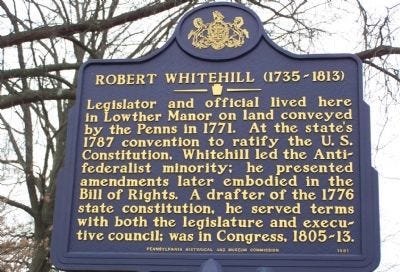

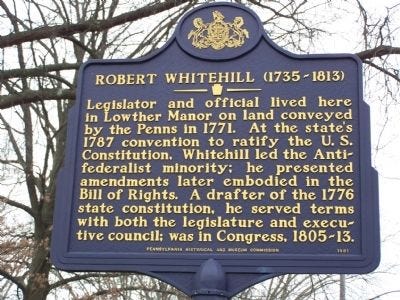

But the framers were also trying to placate the likes of Elbridge Gerry, a Massachusetts antislavery man who objected to the federal militia power on the same basis that Henry did: it took a sovereign power away from the states. Robert Whitehill of Pennsylvania, a middling, non-enslaving, antifederalist farmer from a state that was going off slavery, proposed amendments, including one protecting a right to keep and bear arms (that’s his historical marker at the top). In real life, the Constitution posed no threat to southern slaveholding or to policing the enslaved, and if it had, the Second wouldn’t have ameliorated the threat.

This ancient issue of disarming the populace, going way back into English constitutionalism, gets complicated, like everything else, by slavery in the U.S., but I think framing it as essentially tied to slavery, while satisfying certain lines of thought trending at the moment, makes the issue harder to understand, not easier.

Thanks Bill for reposting this on your Substack - better than Twitter - your end notes are also helpful in gaining clarity over this moment. While it addresses the 2A, I feel that your explanation and analysis lays bare for even the most history challenged among us to understand that the Const Convention was a close wrung thing - like the Revolution itself, there was as many chances for failure as there were for success. Madison, Hamilton et al had an overarching objective which, in the light of history as reality, worked pretty well. The price we have paid, whether the 2A or slavery itself, and voting restrictions were I think worth it given the alternatives out there.

Thank you for this. Would you mind doing what you need to do to get this published In like everything. Would be great if lots of folks knew that the 2A was essentially the first instance of a Hallmark condolence card.