TEMPORARILY UNLOCKED

1. In Memory of Robert Hershon (1936-2021)

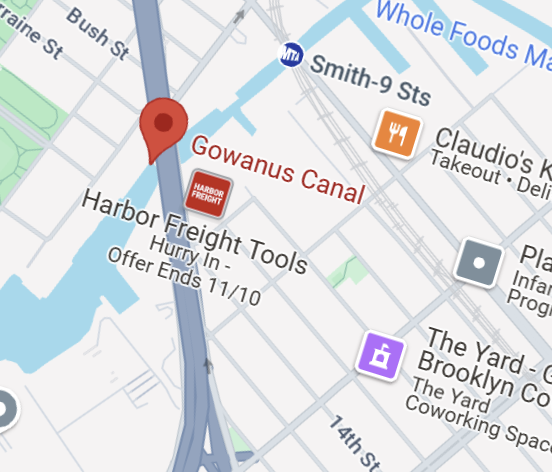

The ghost of Buddy Scotto weeps

on Gowanus’ shore, remembering

bright afternoons here,

brick-and-cement canal-banks

crumbling, bare.

Wooden pilings leaning, scarred and clean.

No barnacles on the hull

of a half-sunk tug,

nothing, in fact, coloring

any nearby surface, no lichen,

let alone moss, and as for the famous

Brooklyn tree,

supposedly unkillable,

it's stinky leaves, which should be

swaying high above

the chain-linked yards

of the shuttered works—

forget about it.

*Buddy also remembers the canal after dark. Preventing life as we, anyway, know it, a thick muck rests maybe twelve feet below a still, black surface whitened here and there tonight by winking work lightsm which secure the darkened hulks, those old factories where Buddy's ghost walks weeping. * Yeah, that Buddy Scotto. Inherited the funeral parlor. Given name Salvatore, a politician, enthusiastic about our end of the borough. Flirted with running for Congress himself, in 'seventy, at forty-two, and backed out not because, or probably not only because the Protestants and Jews gentrifying, as it was called, the brownstone neighborhoods, as they called them, whispered their concerns, probably unsubstantiated, that Buddy was connected. And no, you can't, actually, Google it. But his calling, Buddy’s true calling, turned out to be transformation. He would, he swore, raise the money and organize the clout to turn a postindustrial flow, stopped up at one end, hemmed in at the other twice a day by tidal pushback (“one of the most polluted waterways in the country,” says Wikipedia, which is saying a lot), thick with fecal coliform, pathogens lethally concentrated, and such a scarcity of oxygen that only a weird one-celled organism classified, literally, Extremophile can live there: he would turn the canal and its environs into—quoting Buddy now— into the Venice of Brooklyn. * If I'd been a poet, I might have been the poet of the poisonous, poisoned Gowanus.

2. Not a Poet

The banks of the Gowanus Canal, as many Brooklynites know, have changed drastically and in startling ways from the banks of the Gowanus I knew in my childhood, and in a good part of my adulthood too, as reflected in my poem, above. When I was a kid, there were mornings when you could smell the canal a mile away, which is about where I lived, and while a federal cleanup, underway now for many years, faces major challenges—phase two has begun, with no known end date—I think it’s fair to say that the stench is no longer so bad or so pervasive.

If it were, nothing that’s happened along the canal could possibly have happened.

That’s how bad it once smelled, and neither “bad” nor “pervasive” is the mot juste. Other mots employed to bring that smell to life were employed by Thomas Wolfe, the novelist, not to be confused with Tom Wolfe, the journalist (and sometime novelist). The former Wolfe lived in Brooklyn in the late 1920’s and wrote about it in the ‘30’s:

Oh, that!...It is the old Gowanus Canal, and that aroma you speak of is nothing but the huge symphonic stink of it, cunningly compacted of unnumbered separate putrefactions. It is interesting sometimes to try to count them. There is in it not only the noisome stenches of a stagnant sewer, but also the smells of melted glue, burned rubber, and smoldering rags, the odors of a boneyard horse, long dead, the incense of putrefying offal, the fragrance of deceased, decaying cats, old tomatoes, rotten cabbage, and prehistoric eggs.

I was very excited, the summer I turned fourteen, to come across, in an ramshackle, book-filled, borrowed country house in northwestern Connecticut, Wolfe’s novel You Can’t Go Home Again, where that description appears. I got drawn right in by the exuberant poetry of Wolfe’s prose, which most people now, including me, find annoyingly purple; by the fact that it was a novel about a writer, which now seems like a bad idea, but I aspired to be one too; and by the fact that parts of it were about Brooklyn—and my part of Brooklyn at that—which in my day was called South Brooklyn and got no respect at all.

Wolfe’s passage on the horrible Gowanus smell seemed like such an intimate degree of local knowledge that I could hardly believe our disgusting canal had made it into a real book; also he’d called it “old” in the ’30’s, and I thought of the ’30’s as old. Then, when I told my father what I was reading, it turned out that he’d once been a Wolfe fan himself and knew all about the novelist’s Brooklyn years, including this stunning fact: for a time, Wolfe had lived on our actual street, which was a one-block back alley—so he lived just a few houses away from us—and had even written about it. All of that was thrilling to me as a reader, a writer, a South Brooklynite, a denizen of the alley, and a son of my father.

Until today I believed that the Gowanus also appears in the great New York City reporter Jimmy Breslin’s comic novel The Gang That Couldn’t Shoot Straight, which spoofs the Mafia figures who operated so flamboyantly in South Brooklyn in my childhood, in particular Joey Gallo, aka Crazy Joe. I thought Breslin had the mobsters dispose of a dead or even possibly a live body by chaining it to a jukebox and pushing the whole package into the canal. I can’t find that scene in the book—maybe it’s in the movie? or I made it up?—but I know that we believed, when I was a kid and a young adult, that the remains of dead people lay under that water, if water’s what you wanted to call it, and I don’t think there’s any reason not to believe it now.

The real issue with the Gowanus, though: sheer toxicity. Sometime in the late ’90’s or early ’00’s, with the cleanup effort supposedly already underway, my friend Tom and I took a boat tour on the canal. The craft was smallish. I took great pains to keep even a drop of canal water from getting on me. When the motor started up and churned the water, dead sludge rose slowly from the bottom and spread over the surface. As we putted along, the tour guide gave us some facts about the failure of the Butler Street Pumping Station, which had opened in 1911 (!) amid hopes of addressing pollution, as well as some facts about the political and administrative stalling of later cleanup efforts.

That story should be a novel of its own. It’s really hard to get anything this ambitious done. The forms of pollution and the unfortunate design of the canal are quite particular, and people were aware of the developing nightmare as early as 1889. The canal’s transport function—around the time of the Civil War, hundreds of craft used it every day—had very quickly sparked industrial concentration along the banks: factories making cement, gas, paint, soap, and chemicals, plus more than twenty coal plants, all of them dumping deadly waste on the ground all day and night, thence into the narrow, brief stretch of water closed at one end. The pumping station could do nothing in response to the speed of that buildup.

Later came de-industrialization, which I witnessed growing up without registering it as anything but a kind of mass abandonment, which the poet in me found, as poets have, romantic. At the Gowanus, in Red Hook, on the docks, in the area later revitalized as Dumbo, big works and warehouses stood empty and started to fall. It was a kind of paradise for curious small kids—with nobody around, you could get in pretty much anywhere—and as a teenager and young adult I haunted our own beat-up America right here in Brooklyn, no need to go “on the road” to know disused rail tracks, weedy fields where things had once been made, piles of scrap, and sometimes, as in Ginsberg’s “Sunflower Sutra”—something else I liked then and am not so crazy about now—surprising beauty.

In many places in the country, especially east of the Mississippi and north of the Cumberland, life was once good, in the sense that steady employment enabled many, though by no means all, to attain the comforts of the postwar lifestyle. That was thanks to a man-made ecological disaster producing incredible amounts of noise, smoke, destruction. Massive social and economic losses in the so-called Rust Belt have brought re-forestation, birds chattering, a kind of peace and quiet that can be hard to enjoy if you know what it’s meant for recent generations of people living there.

The Gowanus Canal, as Tom and I saw on our boat tour, can’t deindustrialize. The stuff that went in there, unceasingly, for more than a century, doesn’t break down on its own, has nowhere else to go, kills anything that tries to grow, and pollutes not just the water but the air and the ground. Just being on a boat on the Gowanus—to me, that was an old-Brooklyn in-joke. And yet for all of the grim news we were getting, the tour was part and parcel of the revival of the Gowanus that’s climaxing today.

As an old-Brooklyn guy, which I always was, I was always a revival skeptic. When we took the tour (can it really be more than twenty years ago?), artists were doing the usual thing they do everywhere: opening galleries and studios in a place that was affordable because nobody else wanted to go there. Nothing new—except the outright toxicity of the Gowanus environment seemed to me to push a well-known trend one step beyond sanity. One evening some years later, I attended a birthday party held in a nice, funky open space by the Gowanus waterside, and I marveled with some dismay at what we thought we were doing there. As years went by, I saw kayaks on the canal, was told of bluegrass bands playing on the shore.

Though I hung out around there when I was young, fascinated and moved by the horror and dark comedy and strangeness of it all, I’ve given the twenty-some-year revival a wide berth. Art, bluegrass, poetry: these are among the well-known harbingers of expensive housing that always crowds them out, a familiar process that’s now made its final move into sheer grotesquerie, on the banks of the still disastrously toxic Gowanus Canal.

For it’s not just the water, of course, that’s deadly. “An underground chemical plume” was recently identified throughout the nearby neighborhood, as discussed in a Times article I’ll cite below—a plume of trichloroethylene (TCE), linked, as they say, to cancer, birth defects, Parkinson’s. And yet the building boom, in one of the most expensive places in the country, goes on.

____________

Further Reading

One of many collections of poems by the late Bob Hershon, who died in ‘21.