Here’s a weird thing. I opened a recently published scholarly work on a subject I’m interested and pretty well-versed in, Michael Blaakman’s Speculation Nation: Land Mania in the Revolutionary American Republic (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2023), and came across this passage, in the Introduction:

Why, I wondered, did land speculation mushroom during a period when U.S. colonizers were in many regions rebuffed by powerful Native nations? And why has a period so dominated by elite financiers been so often remembered as a triumph for ordinary land-hungry settlers? Was it possible these things [i.e., elite finance and efforts to gain Native land] were linked?

Well, I said to myself (and in a way to Professor Blaakman), well, yes. That does seem possible.

I mean I’ve been writing about that linkage for years.

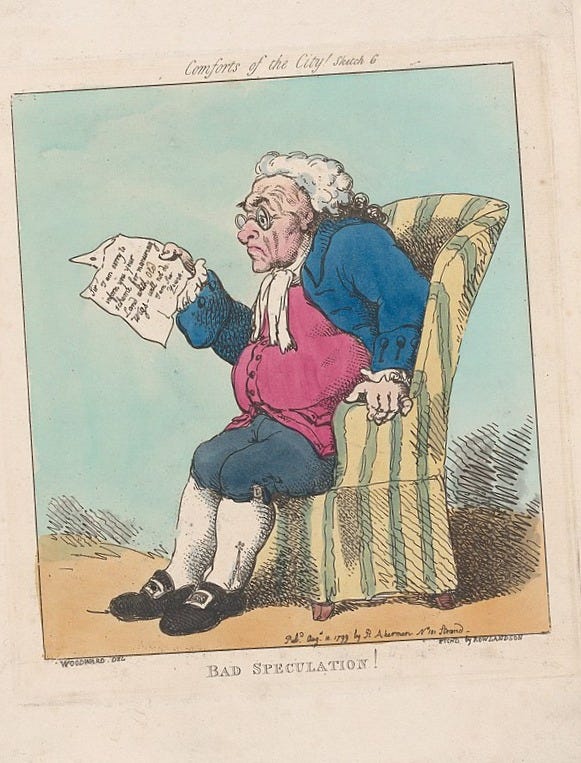

I read on. The thesis of Speculation Nation is that in the new American republic, it wasn't really the settlers but the financial speculators who “rushed to amass huge landholdings under the expectation that Native nations would eventually succumb.

. . . They pitched their land schemes as the solution to the government’s fiscal woes and the gateway to an eventual Eden of republican farmers. In short, they banked on the future of settlement, and in doing so, they fused dispossession with speculative finance.

This was a distinctive form of settler colonialism, a financialized frontier. . . the American Revolution vastly intensified the monetization of Native land.

In a note, Blaakman adds that he hopes, by making this argument, “to resituate the American Revolution within the history of American capitalism.”

Now, if you’ve read my books, and I mean almost any of them, you’ll know that this particular thesis, regarding the drive for what Blaakman calls a financialized frontier, involving war against Native nations on behalf of upscale land speculators, intensifying after the Revolution, and situating the Revolution firmly in the history of American capitalism, does not exactly blow my mind. That's the founding America, the essence of the founding America—the American founding world, I want to say—that I’ve been world-building for twenty years. The Native-dispossession aspect is most fully developed in my 2017 book Autumn of the Black Snake, but the subject is central to all of my books—except maybe Declaration (an error on my part, it should be there!)—including my most recent book, The Hamilton Scheme.

I do know, as you’ll see, that Blaakman and I frame the whole thing differently. And yet in Speculation Nation he explores certain matters also explored in Autumn of the Black Snake that are so granular I won’t delve into them here. An obscure British judicial decision called “Yorke-Camden.” Justifications for expansion into Native land in Jefferson’s “A Summary View.” Benjamin Lincoln’s imagining, while traveling on Lake Erie, an end to the Native populations of the upper Midwest. Stuff like that. And while the landscape and the ideas are intimately familiar to me, and not to too many others, I'm most struck by the fact that the element of Blaakman's thesis which is the most familiar to me is precisely the element of my own work that’s the most unusual among recent accounts of early western settlement.

Which is this idea, which Blaakman and I share: Settlers’ “land hunger” was not in fact the major driving force behind U.S. conquest of Native people’s land.

Many scholars who study the early U.S. in terms of what they call settler colonialism (at this point, I’d like to see that term banned) put a lot of emphasis on the settler side of the expression. They prefer to focus on the nastiness supposedly inherent in the settler himself: toxically white, male, violent, racist, insatiable, unschooled, and therefore reminiscent, in this mindset, of certain negative forces in the U.S. and the world today, thereby revealing, supposedly, the poisonous nature of this country’s and the West’s cultural DNA. In this way, historians endow what’s really a rather abstruse and possibly even boring academic study of the past with the thrills and chills of the 24/7 news cycle and endow the American working-class world of the 18th and 19th centuries with a dark and bloody Cormac McCarthyism.

White-supremacist settlers’ deadly ethos of male violence! This explains everything!

I object to the settler-focused reading. Let off the hook in that account, especially regarding the 18th Century, is a force I take to be far more powerful and significant: the non-settlers, those rich, eastern financial speculators serving in and connected to government, who (like some of today’s academics) deplored the settlers’ no-account backwardness and supposed hyper-propensity for violence, even while hustling land at them. The founding stories I tell are about the unrestrained pursuit of personal gain that defined the established governing class of the early republic and resistance to that class by the white working class. The founding government gave huge, no-bid land grants to insider cronies, ruthlessly exploited the working and settler classes, and fought wars against Native people not, as some like to think, via “irregular” settler-driven militia actions but as a basis for creating the first regular, professional U.S. army.

The ruling class’s speculative ambitions even brought about American independence itself. As Blaakman puts it: “British land policies and limits on westward expansion would become part of the way American patriots justified their choice to declare independence.”

So I guess it’s nice, in a way, to find that I’m not alone in my dissent from the land-hunger interpretation, not alone in framing the big issues of the American founding and U.S. national expansion in terms of high finance and elite speculation, not alone in appreciating certain highly specific features of the historical landscape. For Blaakman does too. He and I even depart from certain Neo-progressive readings that frame the post-Revolutionary period as a counter-Revolution (which I won't get into now). And unlike me, he’s a certified scholar.