TEMPORARILY UNLOCKED

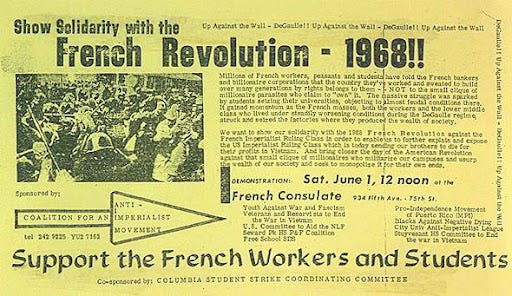

I’m fascinated by the glaring dissimilarities between the situation at Columbia right now and the situation there in ‘68, when the administration called the police, as it’s recently done again [UPDATE: and again]. In ‘68, the protestors took over buildings and barricaded them, occupied the president’s office and trashed it, burned a professor's research papers, and took other violent actions intended not to register dissent, or even to obstruct business as usual, but to destroy the university as an institution. The protestors’ goals were famously summed up in the words of the student leader Mark Rudd, addressed to the university president: “Up against the wall motherfucker, this is a stick-up” (quoting the poet Amiri Baraka).

Argue amongst yourselves, if you must, about which sides(s) on today's campuses are channeling Rudd’s all-in, go-for-broke, burn-it-down, go-ahead-make-my-day attitude, which emerged at a time when student leadership, framing action on campus not as protest but as outright war on a global system, actively sought to pursue that war through violent confrontation with law-and-order forces that were all too ready to oblige. Some today may take positions similar to Rudd’s (or eschew them), but that's a story for another time. What interests me is that so far—and mutual escalation being so dear to our hearts, this may change—the current action has been of a drastically different order from that of the ‘60’s.

What’s striking historically is the relative mildness of what the students, for all of their passion, are doing. I don’t mean mildness relative to the tranquility on campus that the powers that be, or some of the other students—or I, for that matter—might prefer. I mean relative to student actions of the 1960’s.

[UPDATE: The day after I posted this, Columbia students seized and occupied Hamilton Hall. I think the historical comparisons discussed below are further clarified by ongoing events. This building seizure represents an escalation, following a disproportionate crackdown, and following crackdowns at the many other campuses where protests broke out in response to the Columbia crackdown. The ‘68 standoff and ultimate use of force, by contrast, began with building seizures, which triggered a crackdown far less disproportionate to the situation—though possibly more deliberately violent (we'll see) than what went on at Columbia last night.

Given last night's removal of the Columbia protesters by a massed NYPD anti-terrorism force, police control of the campus until the end of the semester, and the administration’s and the mayor’s justifying that operation by claiming the building seizure was carried out mainly by non-students, I’d say that many things remain unclear, but to the point of this essay, I’d also say that last week's police actions at Columbia—triggering, as might have been expected, not only countrywide student protest but also escalations of those protests, which triggered, as might have been expected, escalations of crackdown—make very clear the massive differences between the conditions under which some administrations today feel justified in calling on armed force to respond to nonviolent if disruptive protest (even required to call on armed force, given political pressure) and the conditions under which some administrations did back in the aay.

With reference to the two comments I’ve responded to below: my tactic here was to pick examples illustrative of that difference and assertively avoid doing the kind of survey of new-left agitation and police response in the ‘60’s that the commenters seem to prefer. Nor, by the way, do I suppose that what had been the relative mildness of the 2024 Columbia protest before the escalation makes the Columbia protest exemplary. UCLA looks like a straight-up shitshow right now, with a kind of outright warfare ongoing, in that case, between Israel supporters and Palestine supporters.]

On social media, the writer Rick Perlstein has been discussing, with reference to his book Nixonland, the policing of unrest back then versus the policing of unrest now and pointing out that since 9/11, a riot-gear posture of emergency has become so ordinary that armed-up, militarized, SWAT-like equipment and attitude are common even in small towns where nothing much goes on in the way of crowd action: a militarized crowd-control vibe is simply what much of policing looks and feels like now. People taking issue with Perlstein’s history point to the many times in the ‘60’s when police and the military ran amok and/or harmed or even killed protestors, but I think that just underscores his point. Columbia (‘68), Chicago (‘68), and Kent State (‘70) are examples of uprisings where—the behavior of those cracking down aside—varying degrees of genuinely insurrectionary violence were really going on.

That’s what gets fuzzed out of Sorkinesque liberal memories of the ‘60’s, in which a kind of proto-Obamism prevailed among the youth, misunderstood and overreacted to, in those bad old days, by a conservative establishment now superseded. Such fuzziness is encouraged by some of the people now in their seventies who over-fondly reminisce about their days of student activism, a set that overlaps with those who decided long ago that radical opposition to systems of power is best carried out by having long and successful careers as university professors. The conservative Times opinion writer Bret Stephens, too, complaining in print about the current Columbia protests, compared them unfavorably—and nesciently—to “peace and love marches of the late 1960’s.”

But compare what’s going on at Columbia today [UPDATE: this parenthetical remark is original to the post:] (so far!) with those awful events of Kent State in May 1970, when four students were shot and killed by National Guard. In Nixonland Perlstein brings that situation to life. Protestors at Kent literally burned a university building. When firefighters arrived to put out the fire, protestors cut the firehoses.

As people say these days: Let that sink in. And compare it to Columbia, these days.

In 1970, the scared and exhausted twenty-something guardsmen—straight from dealing with striking truckers, who shot at them—had already been impressed with the notion, by the President of the United States and the Governor of Ohio, that the students were monsters who wanted them dead. Some of the students did a pretty good job of acting like it. In the event, the Guard was [UPDATE: ,pretty literally,] the monster. [UPDATE: I guess I assumed everybody knew this, but lest I be taken for someone who blames the dead students for getting killed, as suggested in the comments, let me underscore the fact that the students who were shot and killed were not only unarmed, as were all of the protesters, but two of the four weren't even part of the demonstration (though if they had been at the demonstration, their killing wouldn't have been any more justified). I'm talking here, as I think should already be clear, about the circumstances under which a particular administration in 1970 felt justified in calling in an armed force, in that case with such horrific results, in contrast to the circumstances under which many administrations today feel so justified. As indeed I went on to say in the original:]

None of that justifies anything. It’s just reality. 1963-1973, roughly, was a time of political violence in America almost unimaginable now—and apparently almost un-rememberable. January 6 is without question a category of violence unique in our history, and uniquely unsettling, but in ‘68 it couldn’t have happened, because that same year, parts of the nation’s capital having been burned down in response to the assassination of Martin Luther King, U.S. Army gun emplacements were at the top of the Capitol steps pointing out at the public.

And yet despite the fact that the protest at Zuccotti Park in 2011, for example, and protests going on now at many campuses, have been so notably different from actions of the ‘60’s, the forces called in nowadays, not to suppress outright rebellions, not to battle outright attacks, but to remove tents and corral and detain protestors, are trained to assume the military posture—punish, crush, win. Once reserved for crackdowns on uprisings, that posture is now seen as fundamental to the nature of policing itself.

Calling out the National Guard used to mean something: things had gotten beyond police ability to manage. Nowadays police may be better armed and more fully trained in combating crowds than the Guard ever was. A young person I was speaking with the other day about these matters pointed out a corollary effect. Because out-of-hand violence still seems the only point, in the minds of many, at which you’d bring in the police, any protest where police are brought in gets defined as violent protest.

… And so we all get a little stupider and less able to deal. …

I’m not going to waste time arguing with anyone who thinks the Kent State students who burned a building, or the University of Wisconsin students and their allies who blew up a building, leaving one dead, had justification—nor with anyone who thinks the Ohio National Guard were justified in killing students. Where would that line of inquiry get us? I’m wondering what it might mean that student action in response to the war on Gaza has so far remained, regardless of some of the oratory, so different from student action in the ‘60’s as to be almost unrecognizable.

As a historian, you're probably used to thinking, "It's a bit more complicated than that." Here are some possible complications.

None of the students at Kent State were armed, and two of the dead weren't even demonstrating. They were walking between classes when the National Guard opened fire. So, while you're right to remind us that the protests were far more violent than the protests today and that they've been sanitized, they didn't pose an imminent threat to lives of the people firing the guns.

And then there was Jackson State, where the killings were justified by the State Police claim that they were shot at, by protestors. The FBI found no evidence of any gunfire except by the State Police. Given the frequency with which the State Police used that word we don't use now, I think it's fair to say that the violence at Jackson State started with Jim Crow, not with students damaging property.

And the union guys shooting at the National Guard? That violence started with the Pinkertons.

The criticism I'd make of people like Rudd, and, in 1968, 15-year-old me was that young white campus radicals inserted ourselves in violent struggles that had been going on a long time, thinking we could play around without anybody getting genuinely hurt. Boy was that stupid. And in the end, incredibly damaging to the causes and people we sympathized with.

We all love and admire Rick’s work, but please acknowledge that there has been much more literature about Columbia, Kent State, Jackson State, etc. since Nixonland (published 16 years ago) that tell a more accurate story of college student protests of the 60s.

Kent State’s own May 4 archive is available online below. I’ll send you my book, a reading list, anything to get people to understand that the students who were killed did not provoke their own deaths.

https://www.library.kent.edu/special-collections-and-archives/kent-state-shootings-may-4-collection