We Are a Band of Brothers

How Did So Many Songs of the Confederacy Get Indelibly Inscribed in My Yankee Memory?

Having posted a while back on the history of “Dixie,” and “The Yellow Rose of Texas,” and the oddity that was “Sing Along with Mitch,” and so forth, I went on mulling over the prevalence, during my youth, of songs associated with the Confederate States of America, and was having, in that context, a Twitter exchange with the erudite writer David Rieff, when we both sort of simultaneously realized that if we chose to, we could burst any old time into a rousing verse and chorus of “The Bonnie Blue Flag.”

For those of you who don’t know it, that’s a CSA marching song.

Happily, it turns out you can’t actually sing a duet on Twitter. More to the ongoing point, though, most people I know in the Land of the Erudite Writer would find belting out a Confederate song not only annoying but downright offensive, for pretty obvious reasons.

Some might be shocked that I know such a song at all. Yet my exchange with Rieff reminded me that knowing Confederate songs—I know other ones too—must be a widely shared condition across a certain white age-group cohort that by no means grew up in “Lost Cause”-nostalgia-cult southern households.

A number of sentimental Lost Cause songs written after the war and throughout the 20th century also exist. I know some of them. But they’re not what I’m talking about now.

What I’m talking about is the fact that the nature of the pop culture that was marketed to pre-pubescent boys, when I was one of them, still makes it seem perfectly natural to me that as a New York City kid, raised by more or less liberal parents, I grew up knowing the words and tunes to songs sung during the Civil War associated both with USA and CSA. “Oh!” I have to consciously remind myself. “That was a long time ago. Boys today don’t grow up with those songs osmosed across their minds and psyches. And I guess some people might even find it kind of strange that I did? Hm!”

Looking back with that kind of conscious distance on a phenomenon that in fact remains nothing but perfectly natural and familiar in my memories (now, as I type, “Bonnie Blue Flag” is playing in my head), I find it odd to remember that the Civil War was a huge, national, cultural deal back then. And the way it was a huge deal was almost solely focused on a brother-against-brother drama.

Brother against Brother! Blue and Gray! North vs. South! Billy Yank and Johnny Reb!

At once thrill, romance, and tragedy, the issue at stake in the war seemed to me to be secession. The whole story seemed to me to come down to the God-given right of a people to govern itself, vs. the biblical warning about a house divided against itself.

We all knew about slavery, of course. We knew it was wrong, of course. Yet I really don’t recall the stark fact of slavery having much emotional impact in the iconography. It was a white story.

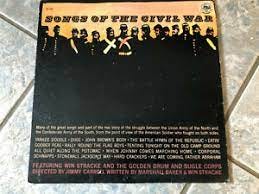

In part that’s because the story was largely communicated, to me anyway, via sheet-music pop songs of the 1860’s, revived in 1950’s and ‘60’s LP versions and linked educationally by a voice-actor narrator. Some of the “songs of the North” do mention slavery—“The Battle Hymn of the Republic” and “The Battle Cry of Freedom” are notable examples—but few of the CSA’s do. That seems a bit weird. When the US first took up the war, its purpose wasn’t to end slavery, and the Confederate states made no bones about fighting to preserve and further slavery.

The most famous Confederacy song that I knew growing up actually does refer to slavery. There’s an endlessly oddball irony in the fact that the best-loved Confederate song was “Dixie,” a pre-war staple of the blackface minstrel stage—a form created and performed in northern cities, set on fantasy southern plantations, and featuring white men dressed up as enslaved black people and singing made-up songs of black life. So in this Confederate song, slavery is indeed the focus, but it’s part of a Yankee fantasy of the slave’s longing to get back to the old plantation. Crazy.

In the war songs that truly came out of the South, one exception to the general avoidance of the subject of slavery, I’ve recently learned, involves “The Bonnie Blue Flag” itself. It underwent some very early bowdlerization. Familiar version(s) begin like this:

We are a band of brothers,/And native to the soil,/Fighting for our liberty [sometimes “our common rights”]/With treasure, blood, and toil [sometimes “we gained by honest toil”] . . .

As the brackets above indicate, a number of well-known variations exist, but there’s one that’s less well-known. An early version’s second line, dumped right away, went “Fighting for our property.”

I can see how the “property” line would have been cut for my listening pleasure in the early 1960s, but that it was cut so early is quite interesting. I’ve also learned that once the US took New Orleans, where the song was published, it became a crime to sing or play it or own the sheet music.

All qualifications and exceptions aside, though, the central drama communicated to me, via LP collections of Civil War songs in the early 1960’s, was the tragic romance of the Blue-vs.-Gray, brother-against-brother, North-South standoff: the emotional intensity of a (white) house divided. The songs hadn’t been about that, of course. It was the mid-20C, kid-oriented edutainment revival albums that mingled the songs and achieved the effect. USA victory and CSA defeat were thus processed through a framework in which both sides had a strong, cogent moral point of view, evinced by similarity of song style. Rallies like “Battle Cry of Freedom” and “Bonnie Blue Flag,“ parlor weepers like “Lorena” and “Just before the Battle, Mother,” and comedy numbers like “Goober Peas” and “Just before the Battle, Mother (Parody Version)” expressed and spoke to emotions shared across battle lines.

And why not? When the focus is on lonely young soldiers on guard duty, say, or revved up young soldiers in battle, or pissed-off young soldiers razzing superiors, the emotions are naturally going to be authentically similar, across all the lines. And in fact the Civil War songs were often parodied and “answered” and appropriated by the other side.

The interesting issue to me now is what cultural efforts like those LP’s had in mind, when they were shaping kids’ semi-conscious impressions of the nature of a big historical event. Why, in other words, do I know Confederate songs? or for that matter Civil War songs generally? There’s more reminiscence to be done on that question, but for now: it’s not just the Civil War LP’s I’m trying to understand. It’s the way the whole Blue-vs.-Gray romance played into my imaginative life, in the years before, say, the Jefferson Airplane did.

So before I close this stab at the issue, I want to note a historical fact, which David Rieff pointed out during our Twitter exchange. It startled me, and it’s begun to explain a lot. Here it is. From 1957, when I turned two, until 1965, when I turned ten, the US was officially celebrating a Civil War Centennial.

I did not know that at the time. I went on not knowing it, until the other month, when Rieff referred to it. It turns out that he and I and many other American kids growing up in that moment got immersed in the Civil War as a result of national cultural policy.

Thinking back, I recall that it wasn’t just the LP’s. There were YA-ish fiction, board games, card games, replica uniforms, etc. That’s also when the interpretive infrastructure of battlefield restoration really took off. What I’ve preferred to take for an early, maybe somewhat perverse flowering of my oh-so-fascinatingly original imaginative life, when I began to forge within the smithy of my soul the uncreated conscience of my race and all that, was in fact heavily sold in, straight at my demographic.

Some very particular centennial agendas and tensions, both nationally and state-by-state, went into framing the nature of the conflict being commemorated. I mean, really: how are you going to “commemorate” something like the Civil War? It can’t be a coincidence that this was when the Civil Rights Movement was beginning to overcome the segregation laws put in place in the South shortly after the Civil War. The whole country was on the verge of some explosive fracturings over a whole bunch of issues. One of the agendas of the War Between the States blitz that I and my kind were subjected to was to refer us, by drama, to an underlying unity, a kind of settlement. Nowadays, happily, we could all sing the songs and all thereby know and feel the points of view. We were a band of brothers, and we’d been through some rough times. That was kind of a kid-friendly pop media version of a long 20C arc I’ve been looking at for a while, related to how Confederate statues got into the Capitol.

Back in the day, if General Lee’s statue hadn’t been in the Capitol, this NYC kid, who knew both sides’ songs, would have wondered why.