In 1798, during the administration of President John Adams, Congress passed the Alien Enemies Act, which gives the president a power to identify, detain, and deport citizens of hostile nations during wartime. The Trump administration has invoked the act in arresting, detaining, and deporting and attempting to deport a wide variety of people.

At its inception, the act was a wartime measure; until now, it’s been used only in times of wars declared by Congress. Yet the act also contemplates a situation short of declared war, in which “invasion or predatory incursion is perpetrated, attempted, or threatened against the territory of the United States by any foreign nation or government.” The Trump administration has therefore framed its targets as engaging in acts of invasion and foreign war.

The presidential proclamation invoking the Alien Enemies Act against, for example, Tren de Aragua (TdA), a transnational gang originating in Venezuela, uses the word “invasion” in its title. The text states that TdA has “infiltrated” the United States and is “conducting irregular warfare and undertaking hostile actions against the United States.” It also states that the gang has supported “the Maduro regime’s goal of destabilizing democratic nations in the Americas, including the United States” and is “closely aligned with, and indeed has infiltrated, the Maduro regime, including its military and law enforcement apparatus.” The proclamation thus seeks to place TdA’s actions within the act’s scope, which is limited to incursions by foreign nations or governments.

The arbitrary nature of the resulting enforcement has been making news. Henrry Josue Villatoro Santos, an El Salvadoran who the administration says entered the U.S. illegally in 2014, is now accused by the Justice Department of being a leader of the transnational gang MS-13. Villatoro Santos had been charged with illegal possession of a firearm, but prosecutors dropped that charge, which would have to be proven, as would his illegal status, in order to shunt him into a deportation effort that the administration claims enables the president to deport non-U.S. citizens hostile to the U.S. on his own discretion.

To identify such targets, the government uses a series of criteria including, among other things, alleged associations, as well as possession and display of symbols, such as tattoos and pictures. Villatoro Santos allegedly had gang-related symbols in his bedroom. Kilmar Ábrego García, who had legal protection from deportation to El Salvador, was nevertheless deported there because the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) identified him as a member of MS-13 based on tattoos, a Chicago Bulls Hat, and the word of an anonymous informant. Still claiming that Ábrego García is a member of MS-13, the administration calls the violation of his legal status an administrative error and claims it can’t get him back from the El Salvadoran prison to which he’s been consigned. That issue has led to standoff between the president and the Supreme Court.

Another sign of enmity is having engaged in dissent from U.S. foreign policy. Under a 1950’s statutory descendant of the Alien Enemies Act that applies in peacetime, Mahmoud Khalil, a Palestinian-born graduate student and legal permanent resident of the U.S., is being held in a detention camp in Louisiana from which the administration intends to deport him. In his case, too, a process of law is underway. The administration had first set out to revoke what it thought was a student visa and then, on learning after arresting him that Khalil has a Green Card, invoked the 1950’s statute instead. Khalil, who has led pro-Palestinian student protests, is arguing in federal court that there’s no evidence to justify his deportation as someone whose presence “the Secretary of State has reasonable ground to believe would have potentially serious adverse foreign policy consequences for the United States,” as the statute has it, and as Secretary of State Rubio alleges.

Also being held in Louisiana is Rumeysa Ozturk, a Turkish graduate student, whose student visa has been revoked, preparatory to detention and deportation, on the grounds that, according to DHS, which has provided no evidence, she “engaged in activities in support of Hamas, a foreign terrorist organization that relishes the killing of Americans.” Ozturk’s case too is being argued in federal court.

Khalil’s and Ozturk’s cases, which regard speech, have antecedents not only in the Alien Enemies Act but also in the Sedition Act, which was passed in 1798 as part of the package famously known as the Alien and Sedition Acts. The section of the Sedition Act that prohibited public criticism of the government, the president, and his policies, is worth skimming in full:

SEC. 2. And be it farther enacted, That if any person shall write, print, utter or publish, or shall cause or procure to be written, printed, uttered or published, or shall knowingly and willingly assist or aid in writing, printing, uttering or publishing any false, scandalous and malicious writing or writings against the government of the United States, or either house of the Congress of the United States, or the President of the United States, with intent to defame the said government, or either house of the said Congress, or the said President, or to bring them, or either of them, into contempt or disrepute; or to excite against them, or either or any of them, the hatred of the good people of the United States, or to stir up sedition within the United States, or to excite any unlawful combinations therein, for opposing or resisting any law of the United States, or any act of the President of the United States, done in pursuance of any such law, or of the powers in him vested by the constitution of the United States, or to resist, oppose, or defeat any such law or act, or to aid, encourage or abet any hostile designs of any foreign nation against United States, their people or government, then such person, being thereof convicted before any court of the United States having jurisdiction thereof, shall be punished by a fine not exceeding two thousand dollars, and by imprisonment not exceeding two years.

This stricture against writing, uttering, and publishing dissent didn’t apply specifically to citizens of a hostile power and other foreign nationals but to everybody in the U.S. It was enforced far more thoroughly than the Alien Enemies Act, which was intended in large part as a threat and resulted in no deportations in the 1790’s. Many U.S. citizens, however, were prosecuted under the Sedition Act.

They were mainly publishers of newspapers supporting the minority Jeffersonian party, which opposed Adams’s Federalist majority. (I’ve written elsewhere in this context about Adams, and about Jefferson’s own arbitrary abuses once he was in office.) In that sense, the act served as intended: it was a government weapon for punishing dissidents and political opponents. The war that supposedly justified such draconian measures was only barely more real than the war that the Trump administration is now claiming exists: a war with France, on the horizon when the act was passed and never materializing; it’s known to students of U.S. history as the Quasi-War. The government’s warlike mood was nevertheless intense, and acts of Congress passed amid war fever gave the president a lot of power, which he used, to stifle legitimate dissent.

Unlike the Alien Enemies Act, the Sedition Act was set to expire, and it did, in 1801. Over the years, however, the legislative branch has pointed to national emergencies involving foreign infiltration and domestic sedition to justify further acts and resolutions allowing the executive branch to carry out detention of U.S. citizens’ without charge (Lincoln’s 1863 suspension of habeas corpus) and suppression of citizens’ free speech and free association, often dovetailed, as today, with immigration law: the Espionage Act (1917), a new Sedition Act (1918), the Smith Act (1940), and the Internal Security Act (1950). The executive branch has also taken action on its own hook, upheld by federal courts, via the doctrine of “extraordinary rendition,” whereby targeted foreign individuals are abducted to a third state where U.S. laws requiring due process and prohibiting torture don't apply. The practice began in the Clinton administration, was developed in the GWB and Obama administrations, and is mimicked in the Trump deportations to El Salvador.

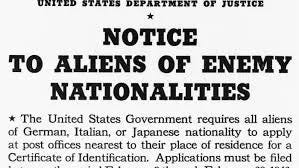

But the Alien Enemies Act itself stayed on the books—a gift from President Adams to President Trump. It was put into real practice for the first time by President Madison, during the War of 1812, when British nationals in the U.S. were required to register with local federal marshals. The next time was 1917-18, with U.S. entry into WWI, when President Wilson required all German nationals to register and interned thousands in camps for the duration of the war (J. Edgar Hoover was involved in that). In WWII came the first significant internment of people more broadly defined as having “enemy ancestry,” under the Alien Enemies Act, beefed up by other statutes. FDR’s Justice Department interned about 11,000 people defined as having German ancestry—some, especially spouses and children, who “voluntarily” joined the internees, were U.S. citizens—about 3000 Italians and Italian Americans, and about 120,000 people of Japanese descent, of whom the majority were U.S. citizens.

That sketch shows that throughout our national history, the detention and expulsion of immigrants considered enemies, in the context of an alleged national emergency rationalizing the absence of due process of law, has dovetailed with violations of U.S. citizens’ individual right to free speech, free press, free association, free assembly, and due process of law. The Adams administration and its Federalist majority in Congress intended the Alien and Sedition Acts to work as a comprehensive package against both aliens and citizens. From Adams’s prosecutions of publishers to the criminalizing of ideas under the Smith Act to the internment of Japanese Americans, the drive to detain and expel aliens en masse has always been inextricably bound up in violating the rights of citizens. Today that mentality is actively fostering national emergencies—wars and rumors of wars—to conjure the usual rationalizations.

The bad history of such efforts should make it easy to ignore the myriad of distractions thrown up by the Trump administration to make the current arrests and detentions feel personal. It doesn’t matter what you think of any or all of the people involved in these cases. Kilmar Ábrego García has been described by supporters as “a Maryland dad.” Casting him as a nice guy is supposed to make the arbitrary nature of his arrest seem worse, but it doesn’t: he could be revealed as a total jerk—some Maryland dads no doubt are—and the principle would remain the same.

It may be easy to have sympathy for Rumeysa Ozturk and Mahmoud Khalil if you’re pro-Palestinian, or a graduate student, or know young people at universities, or have ever engaged in speech contrary to government policy, but if you don’t have any sympathy for them, the principle still stands. It’s pretty easy to have sympathy for anyone arrested for speech infraction—and for anyone rounded up and imprisoned as a member of a transnational gang who isn’t one—but it’s impossible to have sympathy for actual members of transnational gangs in the United States, or anywhere else, who could easily be proven, if the administration bothered to try, to be guilty of mindblowingly heinous crimes.

Sympathy is good, but isn’t the main point. The point is legitimacy in government, without which government itself is nothing but a heinous crime, also carried out by gangsters, but on a mass scale. The reason for due process of law is that if the worst criminal doesn’t have a right to that process—if the most alien person you can imagine doesn’t have that right—then you don’t have the right either.

It’s elementary. It goes back to the beginning. When the Federalists of 1798 called for “natives, citizens, denizens, or subjects of the hostile nation or government” to be “apprehended, restrained, secured and removed, as alien enemies,” they were talking about you.

Well said, a Hippocratic Oath for governments: “The point is legitimacy in government, without which government itself is nothing but a heinous crime, on a mass scale. The reason for due process of law is that if the worst criminal doesn’t have a right to that process—if the most alien person you can imagine doesn’t have that right—then you don’t have the right either.”