When Constitutional-Law Professors Fight

... we without law degrees can learn some odd things.

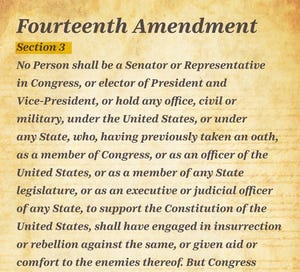

Utter division now prevails between equally well informed and highly regarded law professors over the applicability of Section Three of the Fourteenth Amendment to the presidential candidacy of Donald Trump. (In case you’re not sick of hearing it: The section bars anyone who has sworn an oath as an officer of any government within the United States, and has then committed or aided insurrection or rebellion against the United States, from holding office in any such government.) Lawyers are supposed to differ, of course. An adversarial legal system requires resolving conflicts via verdicts, rendered by judges and juries in light of competing arguments made on the basis of established rules of evidence. But the differences among professors over Section Three, as aired out in op-eds and magazine articles, aren’t being argued on the basis of any such rules. Weapons in this argument include competing assertions, competing definitions of terms, and competing hypotheticals regarding century- and two-century-old history.

And the audience for the argument isn’t a judge or jury but us, the public. Since we can’t reasonably be persuaded, given the style of argument, of either position, we’re likely to go with whichever seems likelier to lead to a political outcome we prefer. While that’s not thinking constitutionally, the nature of both the constitutional argument and Section Three itself may lead inevitably to appealing to the Constitution in this decidedly anti-constitutional way.

One of the most sophisticated manifestations of the phenomenon I'm talking about can be found in an article by Steven Calabresi, the Clayton J. & Henry R. Barber Professor of Law at Northwestern Pritzker School of Law, published in “The Volokh Conspiracy,” hosted by Reason magazine (see “Further Reading,” below). Calabresi is arguing against the position taken in a piece also published there, this one by Ilya Somin, Professor of Law at George Mason University. Here, then, are two highly credentialed professors, both comfortable under the Volokh imprimatur—it’s loose enough to accommodate differences but leans, as the site says, libertarian—at odds not just over the applicability of the section in this case but over what the section fundamentally means, in all cases.

Calabresi believes that Section Three of the Fourteenth applies only to insurrections and rebellions “akin,” as he puts it, “to the Civil War” and therefore not to the attack on the electoral certification process in the Capitol on January 6, 2021. Somin believes the January 6 attack fulfills the constitutional definition of both “insurrection” and “rebellion” under Section Three. I, for what it’s worth, find it easy to agree that the January 6 attack was categorically different from the Civil War (Calabresi) and that the terms “rebellion” and “insurrection” apply to the attack (Somin), but how much is any of it worth, when it comes to assessing grounds for applying the section, or really to understanding the Constitution operationally at all?

Let’s find out. . . .

The way these professorial disputes for the general public tend to go is typified by Calabresi’s underlying a priori regarding the purpose of constitutional clauses:

Yale Law Professor Jed Rubenfeld has written wisely that all constitutional clauses are written with a paradigmatic wrong that is meant to be righted. The Fourth Amendment "right" to be [free] from unreasonable searches and seizures was meant to right the "wrong" of the British colonial general warrants authorizing sweeping searches of colonial warehouses to look for smuggled goods. The Free Exercise Clause was written to prevent the "wrongs" done to Quakers who were executed for heresy by the Massachusetts Bay Colony, and the exclusion from the franchise of Catholics and Jews by the British government.

The paradigmatic "wrong" underlying Section Three of the Fourteenth Amendment was an insurrection and rebellion during the U.S. Civil War that led to the deaths of between 620,000 and 850,000 Americans. . . .

Hence Calabresi’s rejecting applying the section to January 6.

It’s interesting that Professor Rubenfeld has sought to limit the intention of all constitutional clauses to righting specific wrongs along paradigmatic lines established by the wrongs when committed, but that doesn’t make the limitation real, and Calabresi's examples don't prove that it is. The Crown had violated search-and-seizure restrictions, and the federal government was therefore prohibited by the Fourth Amendment from doing the same, but nobody knows better than Rubenfeld, and no doubt than Calabresi, that the state governments weren’t so prohibited by the U.S. Constitution until after ratification of the Fourteenth. Identifying the motivation behind the amendments’ clauses in an errand to right wrongs in an independent America can thus get pretty murky, as Calabresi’s short history of the supposed origins of the First Amendment’s “free exercise” clause shows too. The First, as originally intended, didn't prevent a state government from restricting free exercise, as he seems to be suggesting it did, with specific reference to Massachusetts. The first ten amendments didn't apply to the states; the states’ own processes of church disestablishment, some of them influencing national disestablishment, have complicated histories of their own.

When applying whatever usefulness the Rubenfeld doctrine may have for understanding the first ten amendments to an understanding the Fourteenth, it's important to emphasize the obvious: the theory isn't that the first ten righted wrongs literally committed in the past—as if the Fourth, for example, finally expelled British troops from homes. The idea is that certain clauses prohibit the federal government from committing future wrongs on paradigms established by the British in the past, and in that context, despite Calabresi’s asserting the doctrine as a standard, it doesn't apply to Section Three. Calabresi says:

The paradigmatic "wrong" underlying Section Three of the Fourteenth Amendment was an insurrection and rebellion during the U.S. Civil War that led to the deaths of between 620,000 and 850,000 Americans. That was 2.5 percent of the population or the equivalent of 7 million people today. Section Three does apply to future "insurrections or rebellions", but they have to be analogous in some way to the Civil War. This is the sense in which the words "insurrection or rebellion" are used in the Fourteenth Amendment.

But in Section Three, especially, the wrong to be righted is by no means repetitive of the wrong actually committed, which according to Calabresi is the Confederacy’s “insurrection and rebellion.” The wrong that Section Three seeks to prevent isn’t paradigmatic at all (“troops shall never again occupy homes”; “a confederation of states shall never again rebel”). It’s a potential future wrong orthogonal to the paradigmatic wrong: never shall any officer of a rebellion who broke an oath to the United States by committing insurrection serve in U.S. governments. Nothing about the “righting wrongs” concept really connects, in Section Three, with the paradigmatic concept via which, Calabresi says, the section may be applied only to events “analogous in some way to the Civil War” (whatever “in some way” may be taken to mean there).

Other uses of history get these arguments in other kinds of trouble. When Calabresi and his opponent Somin raise the Whiskey Rebellion and the Shays Rebellion in the context of January 6, they weave the counterfactual and the hypothetical into a double layer of protection against any usable reality. For them, the early-rebellion question seems to come down to something like this: “If Section Three, ratified in 1868, had been the supreme law of the land in 1786-7, when the Shays Rebellion occurred, and in 1793-4, when the Whiskey Rebellion occurred [that’s the counterfactual], would the section have applied to people involved in those rebellions who had previously sworn oaths to the U.S. and state governments [that’s the hypothetical]?”

Both profs imply, at least, that they have ready answers—mutually opposed—to a question that can’t be answered and shouldn’t be asked, if historical and legal cogency is the aim of the argument. During the Shays Rebellion, which both disputants exhibit through the wrong end of the telescope, there wasn’t only no Section Three; there was no supreme law of the land of any kind, no national government in which participants might be barred from serving. Creating a national government was inspired precisely by actions like those taken by the Shaysites; what emerged was a Constitution intended to right a wrong, as it were, reflected in popular uprising and legislation on behalf of democratic approaches to public finance (pre-order The Hamilton Scheme for more on that).

The only imaginable analogous Shays-related counterfactual, then, would be a prohibition enumerated in the 1780 constitution of Massachusetts—that’s the constitution the Shaysites were out to overthrow—barring any insurgent formerly sworn to the state from ever serving in state government again, in which case, I guess, such a prohibition, in fact nonexistent, might have been seen by the state’s court as applying to the Shaysites (in fact the state passed a law to the same effect, a different thing altogether, and a much better idea), but who could possibly care about such a thin and remote set of irrelevant if-thens when considering the thinking of the framers of the Fourteenth, who weren't in fact fantasizing about made-up provision of state constitutions prior to the U.S. Constitution, or when considering the real issue before the Supreme Court regarding Trump?

Who could possibly care? Constitutional lawyers and Supreme Court justices, that’s who. They love taking these trips down national-memory blind alleys. When the issue comes before the court, I expect to [UPDATE: I was wrong about all this:] hear the Shays Rebellion mentioned, fruitlessly, in oral argument and questions from the bench; I also expect to hear lawyers and judges on all sides get the Whiskey Rebellion factually and legally wrong in a fascinating variety of competing ways. (That one did at least come up in the framers’ debate on the Fourteenth.)

Hyper-professorial thinking has led to a kind of speculative absurdity, in which a drily structural approach favored both by the professoriat and, at times, by federal judges, where every issue can be made to yield to pure-logic categories transcending ordinary waking consciousness, gets blended with wet, hot blasts from a fantasized national past. That’s a strange brew. The actual day-to-day political struggles that led to the creation of the very apparatus of law now being pursued in these arguments can never be encompassed by legal-style debate, so the whole effort becomes circular—even meta—with the effect, presumably unintended, though sometimes you have to wonder, of making a mockery of both our history and our law.

_______________

Further Reading

Prof. Calabrasi, Were Section 3 in effect, when would its disability attach to, say, Jefferson Davis: when he signed his state’s declaration of withdrawal from the Union? When he resigned from congress? When his soldiers’ guns fired on Ft. Sumpter? Or wait until his surrender & arrest 4 years later? Or Robert E. Lee: did his ineligibility begin when he resigned his commission or did it have to await casualty reports from Bull Run?