Not an essay on Dylan—I try not to write about him—but a list of stray impressions of a movie that, on general principles (mine), shouldn’t have been made, since my advice against writing about him extends to making movies about him. Anyway, I’ve never seen a good bio-pic of a world-famous musician or other kind of world-famous artist, and I feel my attitudes against writing about him and against bio-pics of that kind—attitudes some would call negative—have developed partly under the influence of some of the things I’ve gotten, all these many years, out of the work of Bob Dylan.

So just for what it’s worth:

Interesting to me that Dylan’s first meeting with Guthrie is so mysterious in real life and that it’s handled so strangely in the movie. Something like the hospital-room walk-in might have actually happened, but if it did, Pete Seeger wasn’t there, Dylan didn’t stay with him overnight, and Woody could still talk. Pretty well-known is that a rapport developed when Dylan was one of a number of young folkies who hung out at Bob and Sidsel Gleason’s house in East Orange, New Jersey, where Woody, suffering from the effects of Huntington’s Chorea, was let out of the hospital on Sundays under the Gleasons’ care. Dylan lived at the Gleasons’ briefly and recorded a famous homemade tape there. The youngsters would play and sing; Guthrie talked, if with increasing difficulty.

Guthrie said a lot of smart things in his life, a lot of very-smart things, and a lot of goofy things, and I put what he said about the teenage Bob in the very-smart category. “That boy's got a voice,” Woody said. “Maybe he won't make it with his writing, but he can sing it. He can really sing it.” Easy for normal people like us to write off, I guess—not just because of Dylan’s writing but also because Dylan was trying, then, to have a voice just like Guthrie’s. But Woody wasn’t like us. To me, his assessment runs deep.

Considering filmmaking choices. The movie’s avoiding the Gleasons’ house and the folkie hangout there in favor of a lone Bobby in a hospital room with the made-up presence of Seeger and the made-up muteness of Woody solves a number of narrative problems quickly and efficiently—which is a problem in itself. I’d complain about the resulting multitude of missed opportunities if I thought bio-pics of this kind existed for any purpose other than missing opportunities.

I also couldn’t help thinking of the possible influence of this very strange hospital scene, from the 1969 movie “Alice’s Restaurant,” shot after Woody’s death, where Seeger and Arlo Guthrie play themselves:

Bobby and Joanie. Man, what a constant total bummer all that seemed to be for both of them—except when performing. Which has never been my impression of the bittersweet, complicated memories each of them has expressed in various interviews and other formats. The less said the better about her jumping his bones after hearing him sing “Masters of War” when everybody but the dedicated folk audience is fleeing NYC in panic over what some reviews have called “the night of the Cuban Missile Crisis” (what?). The film has to make Seeger the main folkie promoter of a little-known Dylan—because that sets up and solves, naturally, a number of narrative issues—and the role of Baez in more or less lifting the boy up and carrying him around and telling everybody how culture-changing he was, when by no means everybody in the folk scene thought so, has been drastically diminished. The question, always: to what end?

I have a feeling those two had some giddy, head-over-heels fun for a while. Not in this telling.

“Maggie’s Farm” went pretty badly at Newport—musically, that is—or it evidently felt that way on stage. The recording we hear today is probably taken from the board, and it’s pretty good, but the P.A. sound going out to the audience was a mess. The band, too, was not in the groove. Al Kooper remembered it as barely rehearsed, even “miscast”:

In the middle of ‘Maggie's Farm,’ somebody fucked up [my guess is Dylan—H] and Sam Lay turned the beat around (played the snare on beats 1 and 3 instead of 2 and 4) which thoroughly confused everyone onstage until the song mercifully stumbled to its conclusion. But ‘Like a Rolling Stone’ was played perfectly and we really got it across. . . . If you've read any accounts of that infamous evening, chances are they centered on how Dylan was booed into submission and then returned to a tearful acoustic rendering of ‘It's All Over Now, Baby Blue.’ A romantic picture, perhaps, but that's just not the way it was. At the close of the set, Peter Yarrow . . . grabbed Dylan as he was coming offstage. The crowd was going bonkers for an encore, as we had only played fifteen minutes! I was standing right there. ‘Hey,’ Peter said, ‘you just can't leave them like that, Bobby. They want another one.’ ‘But that's all we know,’ replied Dylan, motioning toward the band. ‘Well, go back out there with this,’ said Yarrow, handing his acoustic guitar to Bob [in the movie, it’s Johnny Cash, for no even useful reason—H]. And Dylan did. . . . Can you imagine staring in disbelief as Dylan left the stage after fifteen minutes??? Damn right, they booed. . . . But the media misconstrued the whole point. They attributed the booing to Dylan's electric appearance.

Back to Seeger. If you’ve poked around my stuff, you know I’m no fan. And I’ve written elsewhere about him, Dylan, and Newport (broke my rule before I really had one). But watching this movie was the first time I was ever moved by the intensity of the situation Seeger was in. Edward Norton is great, of course. But the decision to focus on that situation has some real emotional and historical payoffs and is handled with fairness to the characters and the issues. I also liked the conflict between Albert Grossman and Alan Lomax. Macho jerks at war seems absolutely right.

Chalomet. Who could possibly have done a better job with the thrust of this project? Damning with faint praise, maybe—but Jesus, it’s really just a paint-by-numbers bio-pic, and it’s about Bob Dylan (so it shouldn’t even exist), and yet he does have his moments. I think the main problems come in the first half, in the folk world. Chalomet is a good mimic. He needs something to work with. Soon Dylan's career was heavily documented—a ton of press-conference and concert footage—but there’s just nothing to go on for the early days, so Chalomet relies on the weirdly withdrawn, arrogant/shy speaking style you can pick up from the Gleason tape and elsewhere; often he’s trying too hard to use it in situations where you feel that nobody ever would have been talking that way. He’s best when being obnoxious, like insulting Baez’s songwriting and berating the hospital orderly: that feels like a credible image of what a young Dylan might have sometimes been like. Or any of us. Once he has the big hair, the mod outfits, the shades, the invention of the rock-star archetype, Chalomet’s got more of what he needs as an actor, and the mimicry can be pretty sharp—fun and funny.

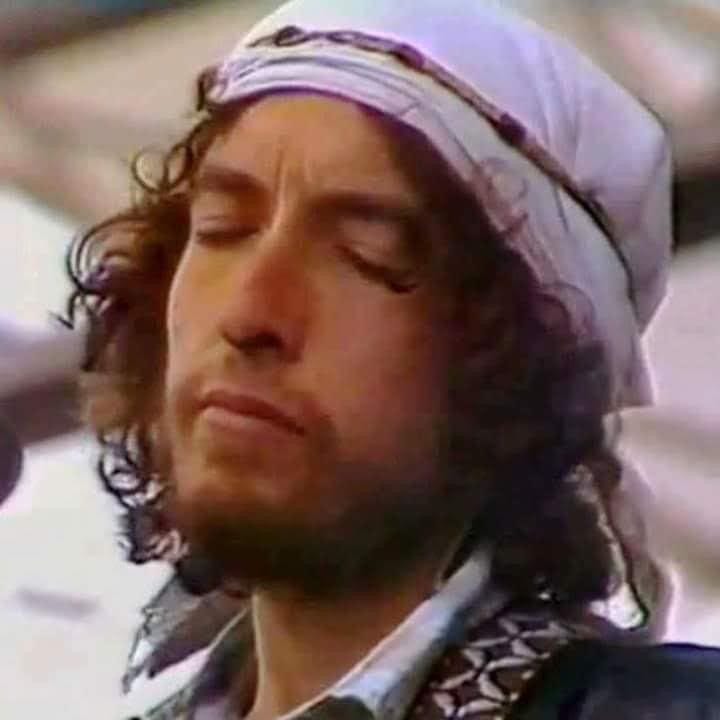

But then why not use those nerdball glasses in the early days? There was a schlubbiness to the still-babyfat real Dylan, teenage out-of-towner, younger than his years and trying way too hard—the character, not the actor—to be Woody Guthrie and Jack Kerouac and Billy the Kid and James Dean, not really pulling it off, and sometimes just goofing around. It’s the guy in the picture above who was claiming he’d worked in carnivals. Which is hilarious. Also relatable.

That guy became this guy . . .

. . . in about ten years, and some other guys along the way, and some other guys to follow, and all in public, and nobody had ever done anything like it before (or has since?). That’s not something an actor or a movie or a book can make happen. Because it really happened, and the only thing that lasts and matters in the end is the music and the theater that came out of it.

For this story, I’ll always think documentaries, not a fictionalized feature, offer the most compelling viewing. I like “Don’t Look Back,” “No Direction Home,” and, for Newport ’63-’65 in particular, “The Other Side of the Mirror.”

I’ve always wondered about Joan and Bob’s seeming fondness for one another in hindsight. I think the actors did great but not sure I felt the proof of that fondness in the writing. Are there any great pieces, books, or documentaries you’d recommend that are really quality on Bob and Joan?